Waiting For Judgment in Springfield, Ohio

Harsh times for America's most famous Haitian community.

Springfield, Ohio is covered in snow and foreboding. The streets are well plowed, but everything else sits under a uniform sheet of white. Needle-like icicles hang from the eaves of houses. Inside them are more than ten thousand Haitian immigrants. Almost nobody is outside. It could be the cold. Or the fear.

Here is why so many eyes are on Springfield right now: Many people have fled violence and poverty in Haiti in recent years. Drawn by a burgeoning community, thousands have settled in Springfield. By almost all accounts, they have helped to revive the flagging central Ohio town, perched halfway between Dayton and Columbus.

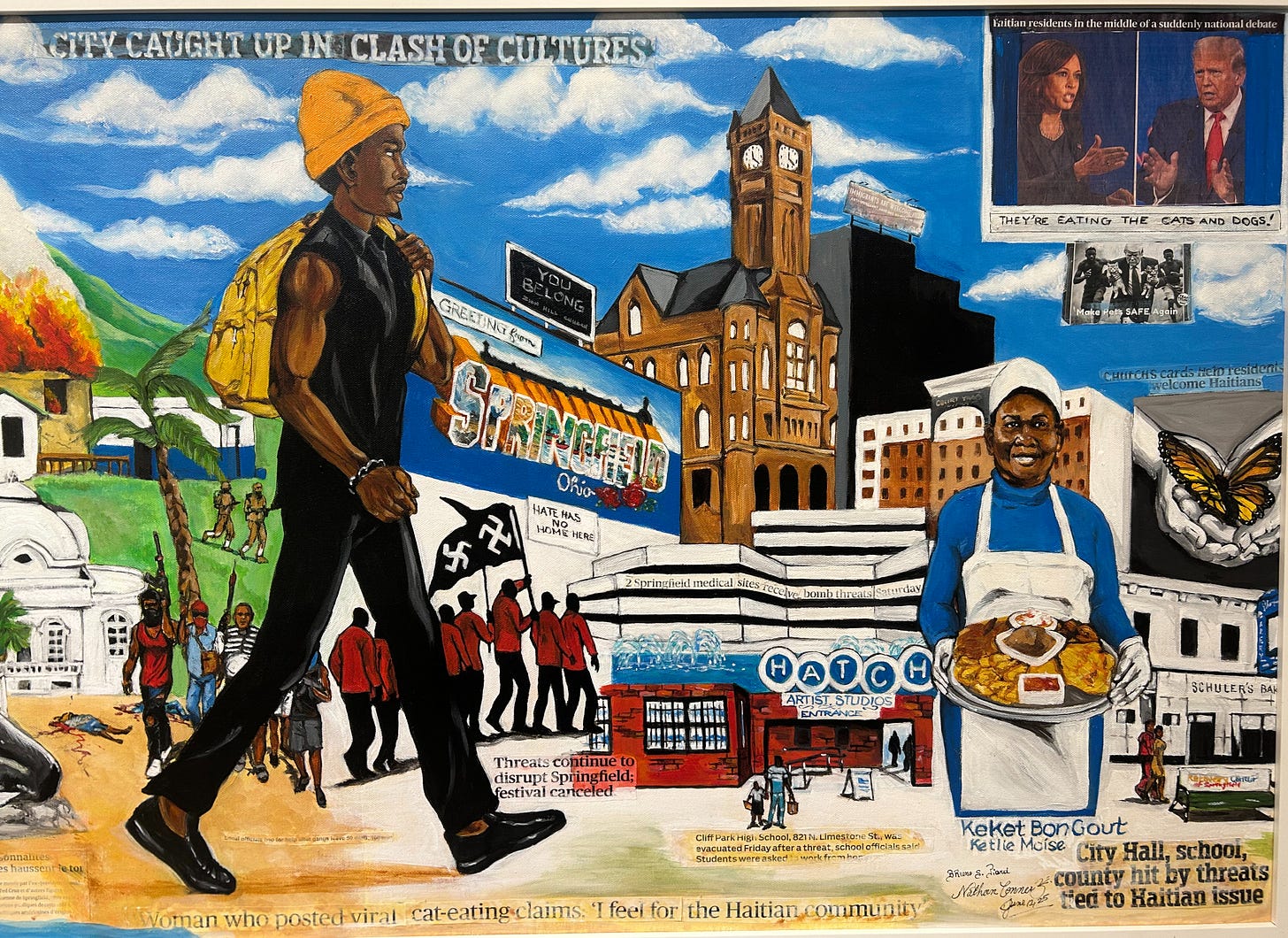

In 2024, racist lies about Haitians in Springfield eating people’s pets began spreading in right wing media. The Trump campaign seized on them, and suddenly they became a national issue. Ohio’s own JD Vance echoed the claims, and then, when challenged, shrugged and said it was okay to “create stories” to get the media to focus on the many dangers that immigrants posed. Springfield was fully transformed from a town into a political symbol.

The ability of Haitians to be here legally rests on a Biden administration grant of temporary protected status. (Considering the United States’ role in Haiti’s history, this seems like the least we could do.) More than 330,000 Haitians are in America under the TPS program. Last year, the new Trump administration immediately set out to end TPS protections for Haitians, among others. After court battles, a judge ruled that TPS for Haitians would expire on February 3, 2026.

As Los Angeles and Chicago and New Orleans and other cities have suffered through invasions by ICE and CBP agents in recent months, awareness of just how Nazi-esque our situation is has grown. This culminated in Minneapolis, where an entire city has roused itself towards massive resistance of an invasion of thousands of armed federal agents kidnapping people off of the streets. Renee Good was killed by those agents on January 7. On January 23, the entire city shut down in a general strike. The next day, Alex Pretti was killed. The eyes of the country focused on the struggle between ICE and the rest of us. And then, right at that moment of maximal attention, it dawned on everyone that in one week, TPS protections for Haitians would end—and Springfield would be in the crosshairs.

Rumors spread that a thousand ICE agents were going to flood Springfield as soon as TPS ended. Ohio governor Mike DeWine told the Springfield school district to prepare for federal enforcement activity, and the Superintendent of Schools told district staff to prepare for a possible 30 days of federal action, and that message, understandably, caused panic. In a city of only 60,000 people, a surge of federal agents on that scale would dwarf anything America has seen before.

Then, at the last moment, came a temporary reprieve. On Tuesday, just before TPS was set to expire, a federal judge blocked it. The Trump administration will run to the Supreme Court to appeal. Until then, the Haitians in Springfield are still legally allowed to be here.

For how long? Nobody really knows. I spoke to Geoff Pipoly, the lead attorney on the case. He doesn’t know. While stipulating that anything is possible from the Trump administration, he said he would be surprised if they defied the court and carried out a big ICE operation in Springfield while TPS is still in place.

Still, he was realistic about the grim set of conditions descending on Springfield’s Haitian residents. For ICE and CBP agents, a city like Minneapolis poses at least somewhat of a challenge in the sense that it is a diverse place, and a random non-white person walking down the street is very likely to be a United States resident. In small town Ohio, Pipoly noted, that is not the case—Haitian residents stand out. From ICE’s perspective, he said, “Springfield’s gotta be like shooting fish in a barrel.” When he came to Springfield this week, he felt himself gripped by the paranoia familiar to residents of every city that has been subject to their presence. “I was at my hotel downtown in the parking lot, looking for ICE agents’ cars—saying ‘there’s an SUV with out of town plates,’” he said. “But then I realized, it’s a hotel!”

The legal pause has not changed the underlying problem facing the Haitian community in Springfield. Viles Dorsainvil runs the city’s Haitian Community Help and Support Center, and is the community’s most visible public spokesman. His group is passing out letters that Haitians can give to their employers, certifying that they are still legally allowed to work. But the fear of what is coming has already arrived. Many Haitians are sheltering at home for their own safety. Community organizations have teams of volunteers delivering groceries to them.

“We tell them to continue to lay low. Because you cannot give yourself the luxury of living as if everything was normal,” Dorsainvil said. “Most of the time, the federal government is not cooperating with the local government to do things. They just go ahead and do what they want to do. And this is why folks have to continue to be careful.”

This is how brutal the situation is: Some Haitian families are so fearful of being deported with no warning that they are making plans to ensure that their children are taken care of. “On our side, we are trying to be proactive. To tell the parents to make the decision to sign a power of attorney to give the guardianship of the kid to a person they know. Because we know that when that kid is in a foster care, automatically that kid is under the supervision of Children’s Services,” Dorsainvil said. “If the parent is being detained and deported, they can take the kid to court to decide her or his future. Most of the time you can find a judge that is understanding… but if you find a judge that is maybe conservative and says, ‘that parent should make better preparation for that kid, we don’t want to give that kid back.’ So this is why we are advising parents that they are the one developing the personal plan to choose a person, a trustworthy person, to make sure that if the kids get home and they are not there,” they will not be at the full mercy of the courts.

While Springfield is the spiritual epicenter of this issue, Haitians across the country are also affected. Guerline Jozef, a human rights advocate who leads the Haitian Bridge Alliance, said that she knows of Haitians already sheltering in place in San Diego, New York, and other cities where ICE has been active. There is an enormous need for resources to face this threat. “We need to be able to hire an army of attorneys to be able to answer to deportation defense. We know that we have TPS holders who have been detained and deported,” she said. “We have been able to get a lot of them released—however, if we don’t get in contact with them right away, we don’t know.”

On top of that, there is a building humanitarian crisis being created due to the deportation machine’s disregard for splitting up families. “We see a lot of folks who were taken by ICE during the ICE raids when they were going to court, leaving behind pregnant women, wives, and children” said Jozef. “So we literally have a sub-class of fatherless children and women who have lost their husband or partner to ICE enforcement and deportation.”

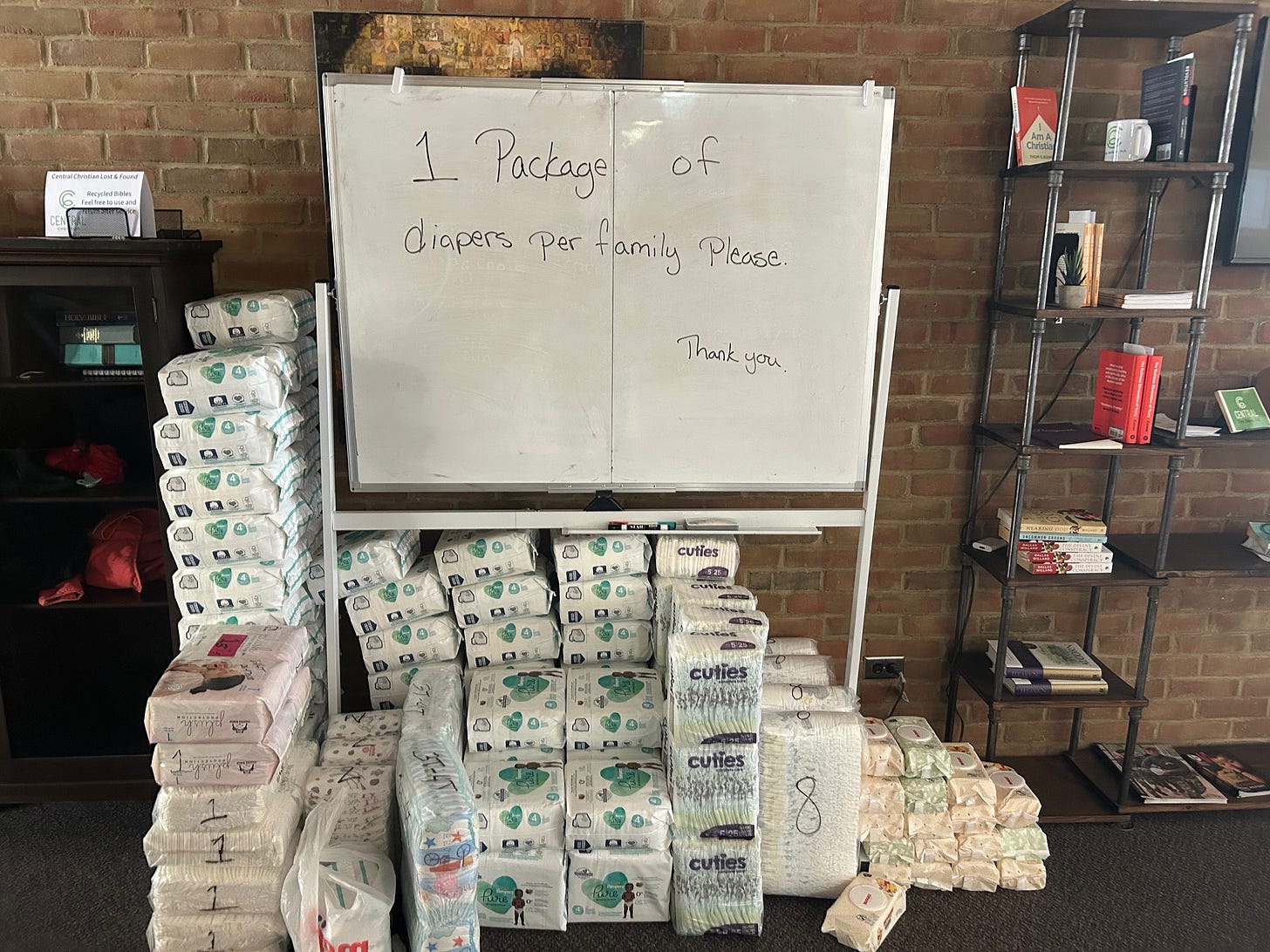

In Springfield, churches have built a robust community network that has been working for more than a year to provide necessary supplies to immigrants, and training local residents in the sort of ICE resistance tactics that have now been well-honed in other cities. On Monday, 1,300 turned up for an event to learn how to support their Haitian neighbors. Now, everyone who was ready for battle on February 3 is standing by, knowing that the battle still looms despite being delayed.

“We are praying for the best,” Dorsainvil said, “but we are preparing for the worst scenario.”

There are a few tourist attractions in Springfield: a Frank Lloyd Wright house, an art museum, an antique mall. And, on a narrow downtown street, a tidy rectangular brick home known as the Gammon House. It was one of Ohio’s only stops on the Underground Railroad. A free black couple, George and Sarah Gammon, built the home in 1850, and defied the Fugitive Slave Act by sheltering runaway slaves there. The Gammons’ son, Charles, gave his life in the Civil War, fighting with the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, which was made famous in the movie “Glory.”

So defying slave catchers and fighting an oppressive government is nothing new for Springfield. It is interesting to observe how different people who come from the same place can be. Some, like the Gammons—and like the Haitian immigrants of today—come to Ohio, work hard, sacrifice, and thereby contribute to making the state a better place for future generations. Others, like JD Vance, leave Ohio, go to Yale, go get rich, move to Washington, DC, and proceed to persecute their former neighbors back home. It’s funny—you never can tell how people will turn out. I guess that’s one thing that diversity teaches us.

More

Our previous reporting on ICE in America’s cities: ICE vs NYC; New Orleans Is Watching You, Fuckers; Hate Has to Scatter When Minneapolis Arises; Intolerable Things.

The Haitian Community Help and Support Center in Springfield is in vital need of funding, and you can donate to them here. Other worthy groups raising money to help the Haitian community in Springfield are G92 and the Society of St. Vincent de Paul. You can also support the Haitian Bridge Alliance, which is litigating these issues nationally.

Thank you for reading How Things Work. There are a lot of things happening in America today. I can’t cover all of them, but I can cover some of them. I’m able to do this work—and to keep this site paywall-free, so anyone can read it regardless of income—solely due to the financial support of readers just like you. If you like reading How Things Work and want to help us keep going in 2026, take a quick second right now to become a paid subscriber yourself, or buy a gift subscription for someone who would enjoy it. Peace my friends.

Great on-the-ground reporting.

PS: “Considering the United States’ role in Haiti’s history, this [TPS] seems like the least we could do.“

Fucking seriously.

Keep up the good work. Rescinding TPS is consistent with the actions of the Trump regime. The regime has abrogated treaties and other international agreements. The only constant is inconsistency. The world no longer trusts us to keep our word.