Executive Pay Is the Skeleton Key

Collective bargaining for thee, but not for me.

Rather than trying to wrap our heads around every sprawling and arcane intricacy of capitalism, sometimes it is easier to just grasp a single piece of it—and once that piece is understood, every other door is opened, and the entire brutal artifice is laid bare. One issue with a direct vein to how every other thing works is “How much the boss gets paid.” It goes without saying that the boss is paid too much, yes. But when you think about it a little it becomes clear that the people who fancy themselves as the captains of the ship are actually the wood-eating shipworms who are consuming the thing from inside until it sinks.

If you have ever sat through the process of negotiating a union contract, you know that the economic negotiations are usually saved for last. Because they’re the hardest. You hammer out agreements on all the other stuff and then you plunge into the money part, where the real conflict lies. Workers want to get paid fairly and management inevitably says it cannot afford to give the workers what they’re asking for. They are not Santa Claus! They have a business to run. During the times when I have sat around with colleagues in conference rooms as these kinds of negotiations dragged on, it has occurred to me that there is a very simple way for the two sides in a negotiation like this to come to an agreement: open the books. In theory, if workers and management could huddle over an accurate balance sheet with all of the company’s assets and liabilities, and could have an open and honest conversation about the company’s upcoming business strategy and its spending plans and what a safe amount of cash reserves are, it would be easy to determine how much money is reasonably available for labor, and from there to divide that pot of money in the fairest way possible. In this scenario, you are effectively running the company like a coop. The financial information is transparent, the values of fairness for everyone who works there are shared, and the negotiation then just becomes a small matter of working out the details.

This is not how it usually goes down. In fact, companies will engage in bitter and costly fights with their own employees for months or years in order to ensure that contract negotiations do not go down like that. Management does not want all of that information to be shared; they want it to be asymmetric, so that they know more and can gain an advantage. Even at public companies, where it is possible to determine many of these economic facts about the business via publicly disclosed financial information, companies will still insist that the information does not offer a full picture, that the union is misinterpreting, etcetera. Besides a desire to hoard information for their own gain, management also does not share the value of “fair pay for all who contribute their labor to this enterprise.” So negotiations that could, in theory, be very short and straightforward matters done with a pocket calculator are hobbled by the greed and secrecy of management, on one side, which often prompts the union to try to just secure the maximum amount that it can, as a desperate attempt to not get screwed.

It is worth drilling down a little on why it seems so impossible to make businesses operate more like coops and less like class wars. Yes, the trivial answer is “People want as much money as they can get.” (I am not a MORON.) But that is not a precise enough explanation to account for the ferocity of many of these fights—especially when it is clear that the collective approach exists and could prevent the fights entirely. Even when we allow for all the investors who need to be paid back, and all the expenses that need be deducted, there is always going to be some amount of money reasonably available in the “WORKER COMPENSATION” column. Why is it such a chore to agree on what that amount is?

The most intractable problem is that the management of your company does not view it as a collective enterprise at all. They view it instead as one of those machines that you stand it as hundred dollar bills blow around frantically, and they view themselves as the lucky contestants whose job it is to pocket as much of that blowing cash as possible. In their view, “making the executives” rich is the purpose of the business. A company does not exist to manufacture cars or sell food or give valuable advice to clients; a company exists to put money into the pockets of the people running the company. The company is not operated to sell whatever it sells, and it certainly is not operated to “provide living wages to as many workers as possible.” It is operated to make executives rich. Everything else is downstream from that. When you view companies this way, all of their actions make perfect sense.

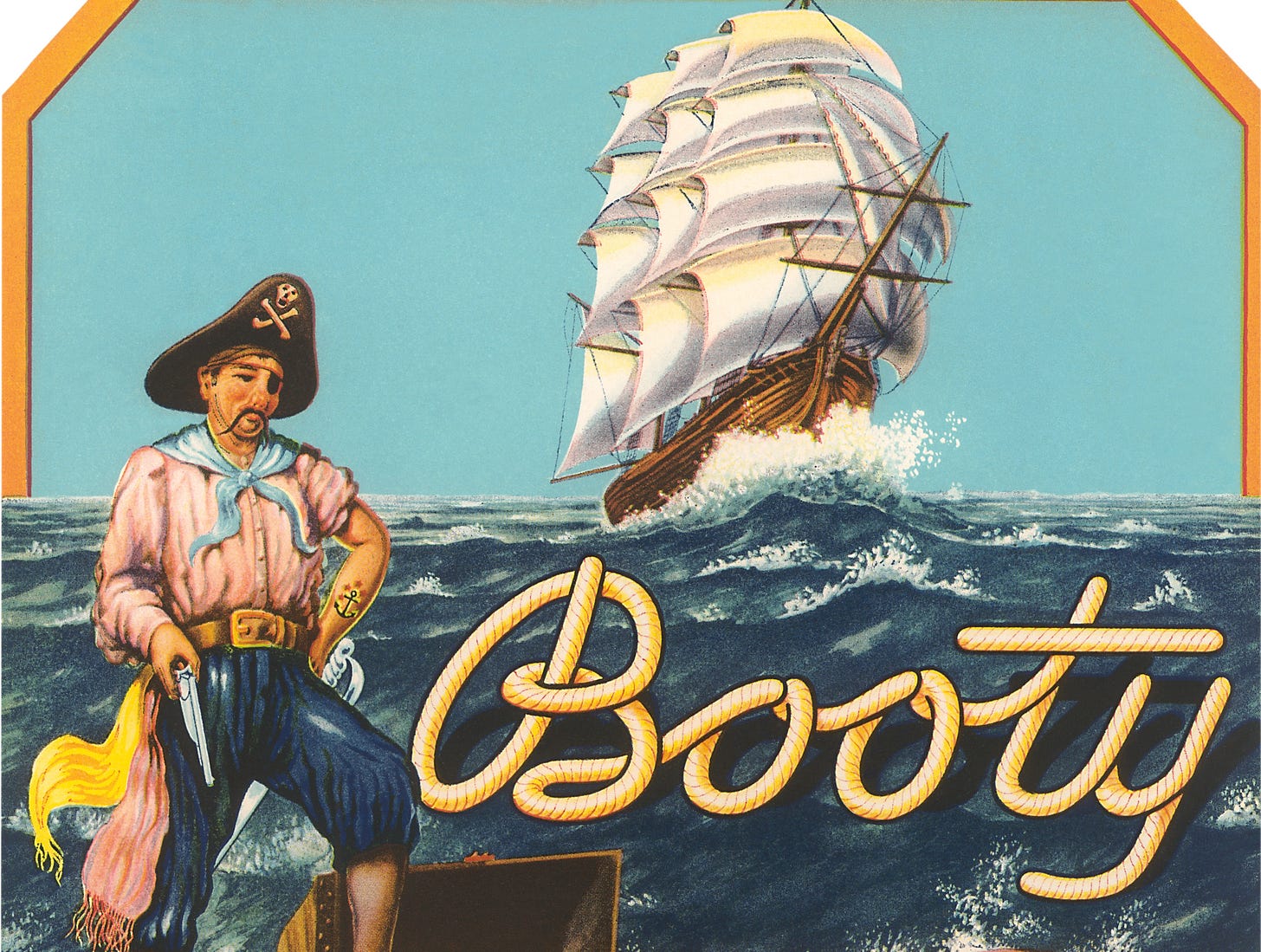

People who run companies will call this analysis childish and reductive, but here is how I know that it is correct: Go into a tough union negotiation, where this a disagreement over economic issues, and suggest putting executive pay on the table as an issue to be negotiated. No! Absolutely not! That is off limits! Executive pay sits in its own separate category, totally off limits from category marked “WORKER COMPENSATION.” Is there any rational reason for this? No, there is not. The reason is that your company’s executives are pirates who see the company’s assets as a treasure chest that it is their natural right to plunder. They take as much as they can get away with. There are plenty of times when adding executive pay into the broad pot of salary money for the whole company would be enough to reach an agreement in a tough union negotiation. But it never happens. The precedent would be too terrifying for the bosses. It would disrupt their very purpose for existing.

Let’s take my own industry, just for example. Just in the past week, LAist laid off 12% of its staff. That company’s CEO saw his compensation rise by more than 50% last year, to $674,000. He was not laid off. The Insider union waged a two week strike to win a $65,000 salary floor. A leaked spreadsheet last year showed that Nich Carlson, Insider’s top editorial exec, earned a salary of $600,000, along with a $600,000 bonus. The New York Times’ newsroom union fought for two years and walked out to win a contract with a $65,000 minimum salary. That company’s CEO was paid $7.6 million last year, and its top five executives collectively earned $18.3 million.

This should be stated as plainly as possible: The job of an executive is not harder than the jobs of any number of workers in any of those companies. We have to report stuff, and research, and write. Executives have to go to meetings and make decisions. Even if we allow the principle that managers should be paid some modest premium to those they manage, all of these numbers are absurd. The fact that anyone who works at a media company could sit across from any of us who work in newsrooms and say with a straight face that they deserve to be paid five or ten or more times the amount that we are paid is insulting. No you don’t. It is a black mark on our society that the public has grown used to this idea. (And these figures are modest: The average major company CEO is paid 324 times what their median employee earns.) None of these executives deserve the respect of the people who work for them. Their greed is harmful. A kindergartener would know that these salaries are unfair. If a company is a lifeboat at sea, the executives are the people stealing the limited rations and gorging themselves as everyone else sleeps.

None of this, I realize, is “news.” Yet I always feel like the utter perversity of it all has not necessarily sunk in. The mere act of collectively bargaining executive pay could revolutionize almost everything about companies are run, which is why it is one of the strictest taboos in any negotiations, one that will make management stalk out of the room in mock anger. If an entry level reporter is paid $65K and a senior writer or editor who has slowly moved up the ranks over many years is paid $130K, then a company executive could reasonably paid, oh, $150K. Maybe $200K. If you are paid $600K, you are stealing $400K from the pot of revenue that should be used to increase the salaries of all of the workers. If the company hits financial difficulties, the salaries of the executives should be slashed first. Before anyone else. That is what leaders do, is it not? Lead from the front? But you all are not leaders, are you? Not really. You are pirates. We see you for what you are. Since you refuse to negotiate, we will just start thinking about how to toss you overboard.

Also

An Axios report found that there have been more than 17,000 media layoffs already this year, the highest number on record. In the current media environment it is very unclear what all those people will do next. I hope that many of them become union organizers. There’s a growth industry.

I have been doing my book edits all week. If I am slower than usual, that’s why. DON’T HASSLE ME. Allegedly, sometime early next year, there will be a book (about the labor movement). Please block out your calendars for the first half of 2024 so that you might attend a book reading because it really sucks when there are only like three people there.

Thank you sincerely to everyone who has subscribed to this Substack. How Things Work is an experiment: Can I, a humble idiot writer, survive in this harsh and unforgiving media environment, without being an executive who earns $600K but still dresses like a big dork? All of you who have become paid subscribers help to keep this site free and open for everyone else to read. Truly, blessed are the paid subscribers—for the collective media of the future stands on your generous shoulders.

Looking forward to your book talk. How about Politics and Prose bookstore in DC?

My routine when a new HamNo post drops:

1) Read the title and the first line: "Rather than trying to wrap our heads around every sprawling and arcane intricacy of capitalism, sometimes it is easier to just grasp a single piece of it—and once that piece is understood, every other door is opened, and the entire brutal artifice is laid bare."

2) Immediately hit the "like" button like I'm buzzing in on Jeopardy

3) Read the rest

4) Go to the comment section and nod vigorously while reading the comments

5) Leave a comment about how much this fucking rocks

I'm taking a couple of writing classes this month after a writing hiatus of thirty years to focus on sending emails. But I think I learn more from reading these posts than I do anything else. The turns of phrase. Incredible. Put up pre-order for that book already! Have a good weekend.