What Will Replace Advertising Revenue?

Probably not hedge funds.

This week a new media outlet launched. Huzzah! A rare and hopeful occurrence in a world of disappearing journalism jobs! One small caveat, though, is that the new publication, Hunterbrook Media, is also—or perhaps I should say “primarily”—a tool for a hedge fund to make money. Its newsroom will publish muckraking investigative stories that the hedge fund that owns it will use to make bets against the companies it is taking down. For example, it is launching with a big investigative story charging massive mortgage lender UWM with fraud. So, in conjunction with the story, the hedge fund has shorted the stock and is also launching a shareholder lawsuit against the company. In theory, the profits from the trading will more than pay for the costs of the newsroom. “We hope our actions drive positive change, as well as a new way to capture the value of reporting,” Hunterbrook writes, “which we believe for too long has gone to everyone except the organizations and the people producing it.”

Why, it’s fairly dripping with socialistic enthusiasm! I’m sorry. Look: it is very easy to criticize a project like this, from a traditional journalist’s perspective. And, if we were living in the year 2015, I would probably do so. I would probably say, “This sort of reporting is inherently corrupt, the motive to damage subjects with reporting in order to make financial gains sits too close to the newsroom for their reporting to ever be free from suspicion of bias, it is hopelessly tainted by the direct and unhidden greed that underlies its existence.” Sure. All of that would be easy to say, in a world where there was a stable journalism industry based on a healthier model. But that world no longer exists. And how healthy was the model that we had before, anyhow?

Hunterbrook Media itself is not going to be the seed that grows into a new media ecosystem. Its focus is too narrow, and it has no real incentive to be a general news source, to do the extra work it would take to cultivate a broad audience. At best it could become a sort of finance-focused ProPublica type of thing, dropping investigative story after investigative story on corporate malfeasance. Matt Levine, looking at the thing from a finance point of view, notes that Hunterbrook has hit upon a rarely exploited form of arbitrage: journalists are cheaper to pay than hedge fund analysts, for doing the same sort of work. Given the fact that the average salary for journalists nationally is probably around $60K a year, and that journalists tend to be able to do a lot of things, this is a pretty solid insight. Journalists are cheaper to pay than many other types of workers who get paid more to do less.

The most interesting thing about Hunterbrook Media is not that it heralds the beginning of a new, hedge fund-fueled golden age of American journalism. (Most hedge funds prefer to suck money out of newsrooms, rather than put it in.) It is that it represents one stab at coming up with a new model for funding newsrooms. Why do we need a new model for funding newsrooms? Because the big tech platforms like Google and Facebook inserted themselves between advertisers and newsrooms and diverted all the revenue out of the media industry and into their own coffers. The advertising-supported model of journalism, which built thriving newspaper and magazine industries for the entire 20th century, is dead. It’s not absolutely dead—there’s enough ad revenue to support a small fraction of the newsrooms that used to exist, which has had the general effect of allowing prestige brands like the New York Times to survive but has decimated local news everywhere—but for you as an average person who wants to read news, you will get close enough to the reality of the current situation by assuming that advertising money is not going to produce the journalism you want to read, as it has been for most of your lifetime up until recently.

So if you care about having news to read, you have an interest in imagining new models to fund it. “Let’s make newsrooms nonprofits, funded by foundations and whatnot,” everyone says. Sure, sure. There are quite a few good nonprofit newsrooms. Love em. But that pot of money, I’m afraid, is only large enough to produce a small fraction of the journalism that was being produced in past generations. Nonprofit publications are not self-sustaining, in the sense that they have to go beg for money every year from whoever in order to keep the doors open. That is why even if you are a raving commie like me and most reporters I know, you should be interested in finding successful new for-profit models for journalism. The profits, in this rubric, do not exist to make executives and investors rich; they are the fuel that keeps the publications open and the reporters paid and the stories flowing.

So, hey—investigative reporting that a hedge fund can trade on? Why the fuck not? It is no more ridiculous than the wine clubs and cruises and recipe databases and other shit that respectable publications today wave around to try to bring in revenue. The holy grail would be something that was big enough and steady enough to replace the portion of revenue that advertising once delivered. Ad revenue for newspapers—which has always dwarfed subscription revenue—peaked at $50 billion in 2006 and the began to plummet. It is difficult to sell $50 billion worth of recipe books. So… what else? What else, folks? Any ideas? Did I see a hand in the back? No? Sorry. Thought I saw a hand in the back.

Here is where I would love to be able to reveal to you the solution to this quandary. However I do not know one. More precisely: I do not know of any source of business revenue that can be wedded to journalism to replace the hole that the decline of advertising revenue has left, and therefore I do not know a purely market-based solution to the decimation of journalism in America, which is a legitimately urgent civic problem. To reiterate— I’m open to ideas! Please write in with yours, and include a check!

The reflexive distaste that many of us feel for a trading-supported newsroom is in fact something of a relic of a code of journalism ethics that was written when publications were robustly funded. It is a pretty good code of ethics! It was built to keep reporters insulated from economic pressures and able to write true things independently. But it has a very strong Let Them Eat Cake quality, as you quickly realize when, for example, the New York Times tells you that you can’t accept any freebies if you want to earn $500 from them for a freelance story, even though you are not their employee, and also you can’t pay the rent in New York City. Likewise, common reader complaints along the lines of “I hate how reporters just dash off stories so fast and don’t put the time in to do all the research” are rooted in the unspoken economics of a bygone era. Hey, do you know who would love to take six months to deeply report and research every story? Every reporter I know! But there are not enough jobs at The New Yorker for all of us. So sometimes we have to write fast. Sorry.

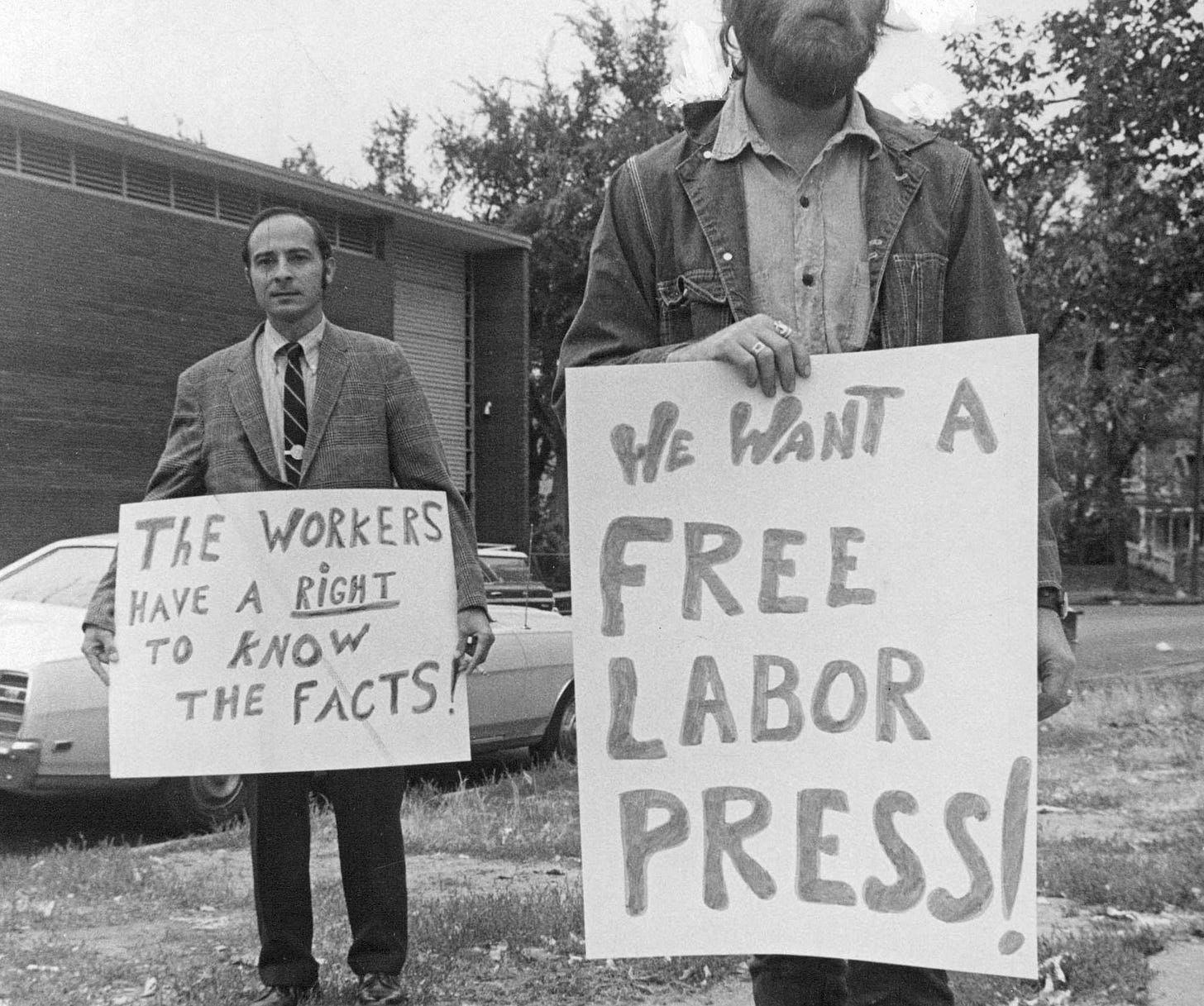

All of this brings me back to a conclusion that I have stated here before, and will now state again: Public funding of journalism is the only way to fix this. Reader subscription revenue is not enough, and recipe book revenue is not enough, and there are not enough hedge funds to build enough newsrooms to replace the amount of journalism that has been lost with the collapse of advertising revenue. Public money is it. Not so I can buy a Jet Ski, although I certainly believe I deserve one, but so there can be at least a few reporters in your town who can write about what all the crooks in your local government are doing.

Maybe if the hedge fund hits it real big, though, they could hire back the 25,000 or so reporters who’ve been laid off. Fingers crossed. In the meantime, please consider becoming a paid subscriber to How Things Work.

Previously, on journalism: We Don’t Work For You If We Don’t Work For You; Do It, Fuckers!; The Utopian Future Scenario of Media.

Also: The Book Tour Is Rolling

I wrote a book about the labor movement called “The Hammer” that many people are saying that you should check out. (And I just published a piece at In These Times yesterday about the strategic importance of unionizing the book industry… synergy.) On top of that I am doing book events across the country where I have gotten the chance to meet many very cool readers and union activists and just generally suave people. People just like you. I am going to be in the following cities in April, you should come out and we’ll talk about the labor movement!!!! And whatever else you like. You can also buy a book and I will sign it. Hell yeah.

Tuesday, April 9: Sacramento, CA—At Capital Books, 6 pm. With the United Domestic Workers. Event link here.

[NEW] Thursday, April 11: Oakland, CA—At the Oaklandia Cafe x Bakery, 5 PM. In conversation with Eli Rosenberg. Event link here.

[NEW] Friday, April 12: San Francisco, CA—At the San Francisco State U Student Center, with DSA SF Labor. Event link here.

Monday, April 15: Los Angeles, CA—At Stories LA, 7 pm. In conversation with Adam Conover. Event link here.

Sunday, April 21: Chicago, IL— “The Hammer” book event and Labor Notes Conference after party at In These Times HQ, 2040 N. Milwaukee Ave. 5 pm. Get your free ticket here.

[NEW] April 23: St. Paul, MN—At the East Side Freedom Library, 7 pm. Event link here.

Hope to see you at one or even all of these events. If you want to bring me to your city to speak, email me.

The publication you are reading is called How Things Work. This is independent media. As you can see, there are no ads here, and there is no paywall here. I only make money for this through the contributions of readers just like you. If you’d like to support the existence of this place, please take a few moments to become a paid subscriber today. It’s good for your karma! And for me, to buy a scrap of bread. Thank you one and all.

You said it before I could comment but the only viable answer at scale would be public funding of journalism. $50B is a small number for the federal government (and it’d be even smaller if states and municipalities took responsibility for contributing to journalism at varying scales).

Well into the 20th century, a lot of small town newspapers survived because local government was required to post public notices of auctions, proposed actions, settlements, judgements and what not in a newspaper. It wasn't a ton of money, but it paid enough to keep a minimal local paper in business. The funders were generally states, cities, towns and counties. The US government had its own Superintendent of Documents, and it is possible that some states did their own printing as well.

By the late 20th century, the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and Washington Post had evolved into national papers. You could get daily delivery in many cities and, even now, they provide world and national news to a lot of papers much like the Associated Press. (The AP was an artifact of the telegraph and railroad era.) If anything, their reach risen with the rise of the internet. The internet has been less kind to local news coverage.

There is a precedent for the government funding local news. Local governments now publish their official public notices online, but these are often disjointed and lack context. I know there is the issue of keeping the press independent, especially as the nation is as partisan now as in the early 19th century. Still, there might be some mechanism.