Unions and Antitrust Are Peanut Butter and Jelly

We need to work together more.

Business people want Kamala Harris to get rid of Lina Khan. Naturally. As the head of the Biden administration’s FTC, Khan has been perhaps the most zealous antitrust enforcer of the modern era. LinkedIn billionaire Reid Hoffman donated $7 million to the Harris campaign, then immediately went on TV and said he’d like her to dump Khan. The inelegance of this move has caused an uproar in defense of Khan. Hoffman would have been better off just attaching a discreet note to his check. Still, he represents a sizable and rich constituency that would like to pull the Democratic Party back towards Obama-era neoliberalism and away from the left’s grasp.

Because Harris has been kept in a closet for the past three years, and because her ascent to the top of the ticket was so sudden, there is a mad scramble on to figure out what she actually believes, and an accompanying scramble to by every faction of the party to ensure that their priorities become hers. Retaining Lina Khan and Jennifer Abruzzo, the general counsel of the NLRB and the greatest pro-labor warrior in the Biden administration, will be a pretty handy yardstick to tell us whether Harris really wants to carry on her predecessor’s progressive economic push. Watching the skirmish over Khan’s future erupt into the news, it occurred to me that there is one constituency that could probably say the word to Harris that would keep Khan safe: Unions.

One thing that seems clear about the still-mysterious Harris is that she appears set on maintaining Biden’s close ties to unions. Yesterday, she spoke at the AFT convention, one of her first major speeches since becoming the presumptive nominee. The AFL-CIO, though it didn’t do anything useful to get Biden to quit, immediately endorsed Harris when he finally did. Harris has been close to SEIU since her days in California, and the union, which has promised to spend $200 million this election cycle, says it is “ALL IN” for Harris. Of the scant information that is available about what Harris’s economic policy priorities would be, one of the biggest items is a huge investment in the “care economy”—child care, elder care, paid leave, pre-K, etc—a top priority for SEIU, which has hundreds of thousands of members working in those industries.

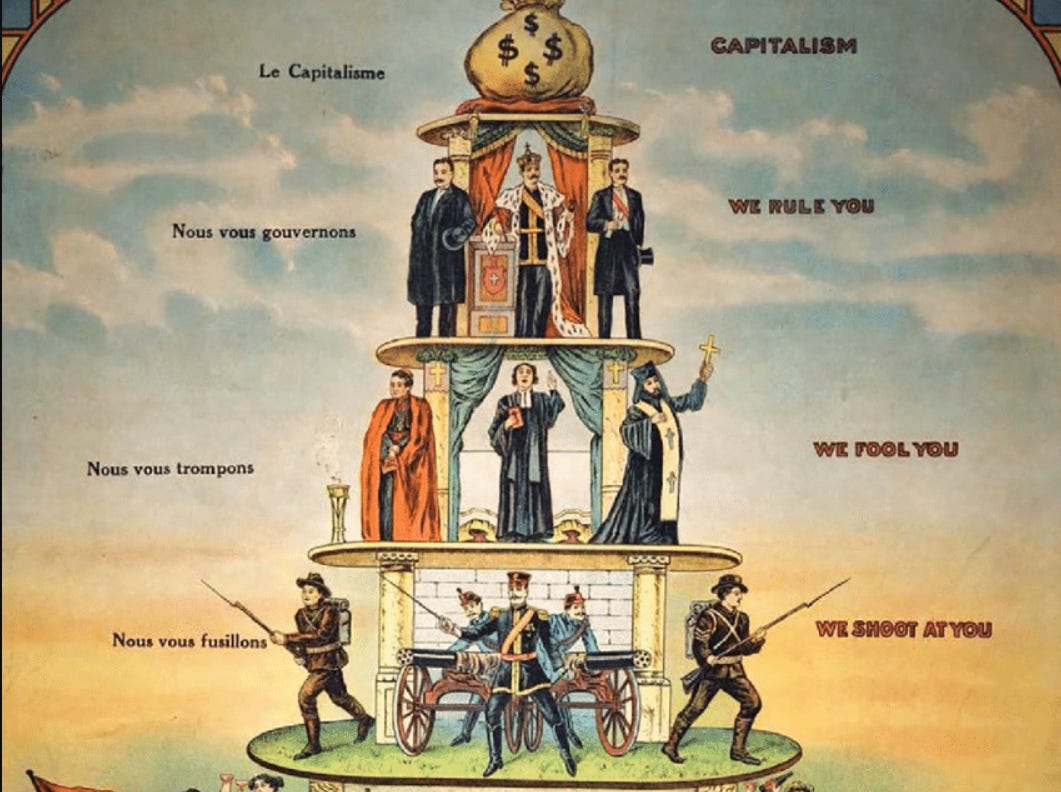

So I feel fairly confident that if organized labor made it clear to Harris that canning Lina Khan was a red line that would piss them off, they could win that fight. But this thought has also made me mull over the divide that exists between antitrust policy and labor policy, and the worlds of people who inhabit each side. The sort of people who spend their careers focused on antitrust issues tend to be wonks and lawyers and come up from one milieu, and labor people tend to come up from the union world, and in many cases they don’t ever spend very much time talking to one another or have particularly deep expertise in one another’s fields. (Warren world vs Bernie world is not an exact metaphor, but close enough.) This despite the fact that they are both engaged in the same work: protecting humanity from corporate power. Antitrust people believe that antitrust is the key to limiting corporate power, and labor people believe that labor power is the key to limiting corporate power. In many ways these two camps are like neighbors who schedule barbecues on the same weekend, rather than just folding into one big event.

Genuine disagreements can arise based on whether you think empowering labor or fighting monopoly power is more important. The clearest example of this is what is happening at Microsoft. Just yesterday, 500 video game workers at Microsoft-owned Blizzard Entertainment announced that they are unionizing. They join more than 1,000 other colleagues who have already unionized. Great. Organizing the lucrative video game industry is important and overdue. The reason it is proceeding so smoothly there is that Microsoft became the first big tech company to agree to union neutrality, meaning that they will not actively fight against union drives, making the work of organizing a zillion times easier. But why did they agree to union neutrality? Well, they wanted to secure support from CWA, the biggest union in their industry, for their 2022 acquisition of Activision-Blizzard, which was very much at risk of being opposed by regulators. And it worked. CWA got neutrality, Microsoft got the support of labor (which had the ear of the White House) for its acquisition, and the acquisition went through. We have seen this dynamic in the airline industry as well, where unions supported the (ultimately unsuccessful) Jet Blue-Spirit merger in exchange for promises of better wages, and also because the unions thought the merger would help prevent even larger competing airlines from crushing Jet Blue and Spirit.

It is far too early to get very deep into the horse trading details of those deals, but you can see the basic outline of what’s happening: Antitrust people see these mergers as dangerous consolidations of corporate power to be opposed, and these particular unions saw the mergers as opportunities for themselves and their members to get stronger in specific ways, and were therefore willing to lend support. There are too many unique aspects of any particular merger to generalize this out to all cases, but it does highlight two different underlying ideas of what is best for working people. (Standing disclaimer: Do not send me wonky emails complaining that my explicitly overbroad generalization is overbroad!) Antitrust people say “Don’t let corporations get too big and powerful in the first place” and labor people say “We need to take every opportunity to build strong unions which will ultimately be the countervailing force to corporate power.”

Of course, unions oppose mergers more than they support them, because they know stronger companies are better at crushing workers. Microsoft, looking out at a time when Starbucks and Amazon union drives were racking up a ton of sympathetic press, just chose the savvier path of trying to bring unions into the fold. One way to weigh the consequences here is to do a little thought experiment: let’s say CWA unionizes essentially all of Microsoft’s non-managerial employees, and at the same time Microsoft, a $3 trillion company today, continues to grow and expand its market dominance. So maybe you end up with a very strong and influential and well compensated 200,000-member Microsoft union and a $6 trillion company with mind-boggling globe-spanning reach. I’m not suggesting there is an obvious answer here. I tend to think that in the long run it is foolish of unions to acquiesce to these expansions of corporate power even if they get gains in the short run, because inevitably the damage done to the broader society will outweigh the gains for those workers. But the answer to this question really depends more on how inherently dangerous and evil you believe international corporate power is than it does on hard evidence that you can spit out on a spreadsheet.

I’m not saying anything revelatory here, but antitrust and labor need to be on the same team. More than they already are, even. Whenever the AFL-CIO and Lina Khan find themselves on the opposite side of an issue, it provokes in me an extremely strong sense that both of us are being played—two starving people forced to fight for a scrap of bread by a cackling wealthy villain. More precisely, it probably reflects a desperation on the part of a labor movement that has gotten so weak that we become willing to strike dubious bargains to claw our way back up. And again—maybe this is the right call! If you accept the presence of normal union busting and the labor laws that currently exist in America, the prospect for unionizing Microsoft is almost nil. Like “unionize Google" or “unionize Amazon,” it is more of a statement of a long term goal that will require enormous investment of not just organizing resources but also political capital to change the underlying conditions that make it hard to do. Today, though, unionizing Microsoft is more of a question of applied organizing resources than anything else. It can conceivably be done. (At least until CWA unionizes enough of the company that Microsoft executives get nervous and scrap their union neutrality pledge, which I bet you $5 will absolutely happen one day.) Is that reality worth the price?

Global capitalism is a beast. Even if the US labor movement was twice as strong as it is today, it would be very hard to deal with Amazon or Google or other companies that span the globe and are worth hundreds of billions or trillions of dollars. There is a very real danger that multinational corporations supplant national governments as the dominant source of power on earth. This is the future that antitrust people are fighting against. An interesting example of how this affects unions can be seen in the ongoing fight between Tesla and unions in Sweden. There we are seeing the clash between the mature and humane and long-standing Nordic system of labor rights, and the unyielding ultra-capitalist sensibility of Elon Musk. Neither side wants to break. The final outcome of that dispute will be a valuable data point regarding the question, “How capable are multinational corporations of bending entire national governments and cultures to their will, these days?” Fun!

There will always be some ineradicable incentive for unions to do things that benefit their own members even if they do some vague harm to society at large. Corporations will always try to exploit this incentive for their own benefit. It is easy to say in an abstract sense “Unions shouldn’t give in to that,” but in the real world, it is not easy at all. Should the United Mine Workers demand that coal mines shut down, because of the environment? Should the Machinists union tell Boeing to shut its factories where its members manufacture weapons that are used to blow up poor people on the other side of the world? Etc. Antitrust issues can sometimes be seen as just another big picture dilemma that does nothing to help working people put food on the table right now.

In lieu of solving this timeless tension in today’s little blog post, let’s think about the more modest goal of how antitrust and organized labor can work together more effectively. First, we all have to realize that we’re all part of one holistic policy goal. We think that allowing corporations to proceed unchecked down the road to ultimate power is a bad idea. It is bad for workers, who will be crushed, and it is bad for governments, who will be co-opted, and it is bad for all citizens, who will suffer as corporate power sweeps away regulations and rearranges all of society to benefit shareholders at the expense of everything else, like AI gone awry. Organized labor should make it a point to use its own political capital—a very real weapon, if Kamala Harris wins the White House—to support antitrust efforts and protect its enforcers. And the antitrust world should correspondingly recognize the fact that simply limiting corporate power by fighting monopolies will never be enough; unless there are unions inside of the companies to constantly exercise power on behalf of the workers, there is no actual institution that will be carrying on the fight to prevent companies from just proceeding right back down the same harmful monopolistic path over and over again. We’re peas in a pod here. Don’t want huge companies and their idiot billionaire bosses to run the world? Break them up, and unionize them. It’s the best program we have.

Maybe we need an antitrust-and-union people happy hour or some shit. Let’s be friends.

Related: It Is Simple for Companies to Treat Employees Ethically. And Yet; Every Pay Bump Is an Admission of Guilt; Corporations Do Not Have Any Rights That We Don’t Give Them; When Unions Back Corporate Mergers, Workers Lose.

I wrote a book about the labor movement and how it can save the America. It’s called “The Hammer,” it’s available wherever books are sold, and I bet you might like it. Am I still going around talking about it? You better believe it! I’ll be at the Brooklyn Book Festival on Sunday, September 29. (That’s in Brooklyn.) I’ll also be speaking at the Wheeling Reuther-Pollack Labor History Symposium on August 31. (That’s in West Virginia). I should have a few more events to announce in the coming weeks. If you want me to come to your city and talk about the labor movement, email me.

Thank you to everyone who subscribes to How Things Work. I started this publication after I finished reporting my book, because the traditional journalism industry is collapsing—thanks to evil corporate power! Synergy! This place is 100% funded by readers just like you who choose to become paid subscribers. I’m not holding a gun to your head. I keep this place paywall-free so everyone can read it. But my ability to do this and pay my bill is completely dependent upon the support of readers. If you like this site and want it to continue to exist, please take a quick second now to become a paid subscriber. Modest price, good results.

I've often thought the best anti-hero would be the laughably evil billionaire who explicitly states his intentions so that people quickly turn against capitalism. (not that I think that's what Hoffman is doing)

I recently read Dark Money and have a post coming out about it Sunday, but what really struck me in the book is how so many evil billionaires learned quickly that most people actually hate their ideology, so they told all their wealthy friends in donor calls "Hey, what we want is unpopular. We have to disguise our intentions and make people think what we want is actually good."

In a perfect world, yes! Totally! Antitrust benefits mostly the same people that Unions benefit! But, and you discuss it but I don't think enough, Union members will vote most often for their best interest. And sometimes their best interest is antithetical to antitrust. This will probably always be the case until Union membership is strong enough to survive strong antitrust enforcement.

But for now it's just the state of things, and I think that's okay. I don't see it as fighting over scraps from a wealthy villain, but rather two competing forces pulling at corporate dominance. I'd bet a bunch of money that Microsoft would have rather not gotten out of CWA's way but did what it had to do because of the threat of antitrust. This is a good thing! At least, it seems like a good thing! If the end result of antitrust is to drive more companies to embrace Unions, that's at least an acceptable outcome, right? Not perfect, but acceptable?