The Public Good, Not Patriotism

Journalists don't work for the United States of America.

Who does a journalist work for? You work for your editor, sure, and you work for your employer, but more importantly, you work for your readers. Even more than that, you work for the public. You work in service of the belief that everyone deserves to know about the things that affect their life. You work for the good of humanity.

This is a grandiose and overly flattering way to describe a job that consists of sending a lot of emails, but it is useful in that it helps to crystallize in a journalist’s mind who you do not work for. You do not (although you are obligated to treat them fairly) work for the people that you write about. You do not work for your advertisers. You do not even really work for the interests of your own news outlet, which is why credible publications do things like “report out long stories about how Jayson Blair made up a bunch of fake stuff that they foolishly published.” Such self-scrutiny may make the publications themselves look bad, but it is in line with the belief that the public deserves to know when they have been duped.

Any job that is supposed to serve the interests of the public necessarily demands a set of moral and political judgments about what the interests of the public are. For journalism, which deals in information, those judgments often consist of determining where power lies, and how it is being used and abused. Much of journalism is reporting on powerful people and institutions, because wielding power of all sorts is an act that affects the lives of the public, and the public deserves to know about what is affecting their lives. This mandate to tell the relatively less powerful public about the activities of the relatively more powerful actors who are doing the things that are shaping their world is the origin of the “afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted” orientation of journalism. It is not that journalism is inherently out to destroy the powerful. Rather, it is that journalism is bound to tell everyone exactly what the powerful are up to, and that is one thing that the powerful really, really do not like. (The gap between what the powerful are doing and what the powerful would like everyone to think they are doing is how the field of public relations came about.)

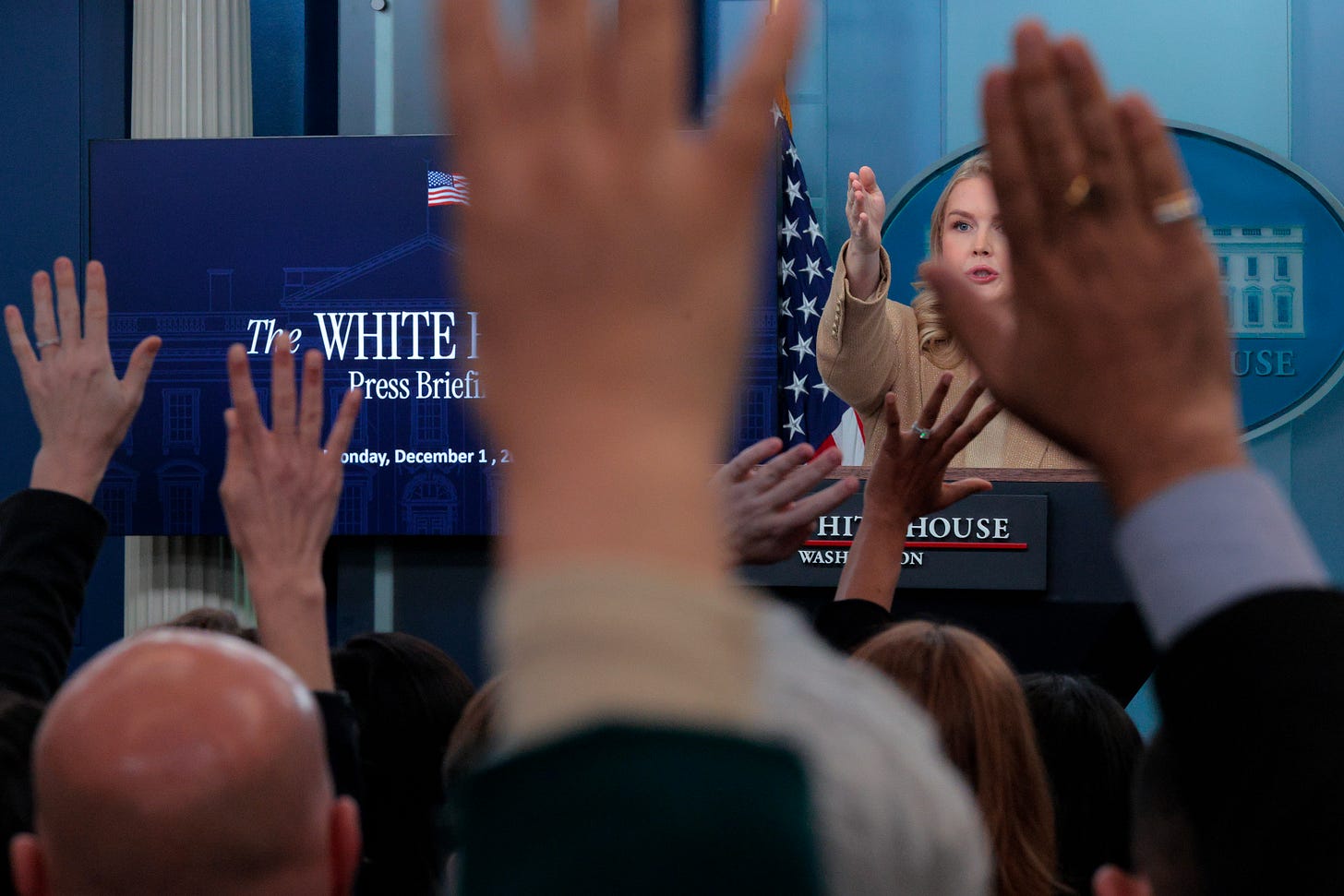

With this in mind, it is easy to name one institution that journalists absolutely, positively do not ever serve: The government. The most powerful institution of all! Telling the public what their government is doing is the single most important task of journalism. Whether you like the people running the government or not does not change that mandate one bit. The government may be doing good things or bad things, but journalists believe that the public should know what those things are either way. Because governments tend to want to keep a lot of stuff secret, journalists work constantly to unearth secrets, and, if they are relevant and important and meaningful, tell them to the public. People who find this distasteful should simply work for the government rather than working in journalism.

“The New York Times and Washington Post learned of a secret US raid on Venezuela soon before it was scheduled to begin Friday night — but held off publishing what they knew to avoid endangering US troops,” Semafor reported this week. This sort of self-censorship of military secrets has a long and sordid history in American journalism. It is not new. Nor is it new for the nation’s leading news outlets to agree to White House requests to hold back reporting in the interests of the troops. What it is, however, is antithetical to the purpose of journalism. It indicates either cowardice, or a loss of perspective.

At least 80 people in Venezuela, including civilians, were killed in the U.S. strikes on Friday night. I bet they would have liked to know that they were coming. Are U.S. troops more important than them? If so, why?

You can see how these questions demand that certain unspoken value judgments be made explicit. One answer, given during wartime reporting, is “in order to be able to report from a war zone we must subject ourselves to certain restrictions on what we can say and when.” Fair enough. Was that the case here? No. Here, we had a unilateral act of aggression by America towards another country, in peacetime. Using the tools of journalism, you can also learn that the president who ordered the attacks is unstable and ill-informed; that the attack itself is illegal under international law; and that the lives of hundreds of millions of people across the Western hemisphere may be indirectly impacted by the attack and its political fallout. I am not trying to pretend as if there is never, ever a government secret that should not be immediately reported to the world. Context exists. In this case, the context overwhelmingly shows that the information in question was a matter of public interest. The decision to hold it had nothing to do with serving the public interest. It had to do with serving the interests of the U.S. government.

In journalism, patriotism is like alcoholism—we all know it’s present in newsrooms, but it leads to dreadfully poor judgment. We should be working to eradicate it, not celebrate it. If you sat down the top editors of the New York Times and Washington Post and put the thumb screws on them, of course they would admit that they report from a pro-American perspective. Whether this is a consequence of cynically protecting their own interests or of genuine mental capture by the sexy allure of bald eagles does not really matter. What matters is that it is a profound flaw in the way a publication operates. We serve the interests of humanity. Do we want America to “win” every war they are involved in? No. We want to tell everyone, everywhere, things that are important to them. We are neither soldiers nor cheerleaders. Every waving flag graphic that adorns a cable news show is an abomination.

When you’re doing journalism, you’re not an American. You’re a journalist. You don’t work for the army. You work for the public. Have some self-respect.

More

Related reading: Nations Are People; The Patriotism Trap; It’s Not Looking Great For the Press.

As what is delicately called an “opinion journalist,” I have the privilege of offering my conclusions to you without doing quite so many contortions for the sake of appearances. If you are alarmed at the direction of America today, I urge you to unionize your workplace, in order to strengthen the labor movement; to join DSA, in order to strengthen the political left; and to, you know, do nice stuff in your community, like feeding the homeless, because good things are good. If you want a longer explanation of how we got here and a path out, you might like my book “The Hammer,” available for order wherever books are sold.

The publication you are reading, How Things Work, is independent. I have a somewhat smaller budget than the New York Times. This site has no corporate sponsors, and it is free for everyone to read. How do I do that? I do it thanks to the financial support of readers just like you, who choose to be paid subscribers in order to help this place continue to exist. If you like reading How Things Work, take a quick second right now to become a paid subscriber yourself for 2026. I am told that it feels great and bestows you with a newfound confidence and attractiveness that is impossible to ignore. Thank you all for being here.

A lot of people's brains shut off when the topic of US imperialism comes up. Including in the brains of liberal journalists, and liberals in general. Everything in their heads has to be consistent with the assumption that this country ultimately means well. If we do something bad, that's somehow an exception, an oopsie-woopsie, an oversight. It's not what defines us. These things are framed as a "betrayal of our values".

They do not understand in their hearts what the United States actually is. You are what you do. What are values that you constantly betray? This violence is what defines us. The implications of the United States being a rapacious gangster state are very dire. The conclusions you have to draw after that is that we do not live under any authority that can be justified as morally defensible. That's a really bad feeling.

I think until journalists, and people more broadly, start to have a feeling of true hate in their hearts for US imperialism, we will not see much progress in domestic affairs either. If you can't be honest about who you are, you can't really be honest about how you get to a better place.

I worked in newsrooms for 20 years, including one national cable news outlet that is not Fox News. My feeling is that withholding information like the Venezuela operation is also dictated, to a large degree, by the expectation that doing so would result in outrage by a large portion of the public - directed not at the administration, but at the media outlet for "endangering the troops." It would create a loud and long-running talking point for the right, result in loss of advertising, harassment / threats to staff, etc.

I'm not suggesting that the decision to sit on the story was morally or ethically justified. But it does show the importance of independent media in these matters. Major news organizations that are beholden to advertisers, shareholders, etc. are forced to make decisions like this.