The Distance Between You and the Revolution

Getting people to care about labor reporting

This week, In These Times finally put online a feature that I wrote about a burgeoning reform movement inside one of America’s biggest unions. I would like you to read it. I bet that you can already see the problem here. “You,” as a statistically median person, are unlikely to care about a burgeoning reform movement inside of one of America’s biggest unions. I say this with confidence because 90% of working people are not union members, meaning that you are unlikely to be predisposed to have an interest in unions, and further because “internal union reform” has the dreary sound of an inherently boring topic that you might turn your attention to only if you were forced to by some cruel college professor, and further because I have been a labor reporter for a long time and I know based upon long experience of looking at the traffic numbers on stories I write that these things are true. You—a good progressive! An educated person! You care about things, in the world!—may insinuate that you would read a story about internal union reform, because it makes you appear to be someone who is intellectually curious and deeply engaged in the vital issues of the working class, but then when nobody is looking, there is a very good chance that you will click out of that story after a few paragraphs in order to rewatch the video about the bulldog who is obsessed with bowls.

Don’t lie to me. I am watching you at all times!

To varying degrees, this is an issue that all journalists wrestle with. Some have it easier than others, though. Sports reporters? People will read that shit. Built-in audience of obsessives surrounded by a large audience of people with at least a general interest. Daily news reporters? They have the advantage that they are writing about, you know, the news of the day, which is by definition something that should be of interest to the majority of readers. Politics, entertainment, money—all of these beats are at the front of the line to claim their share of attention.

The more niche a beat is, the more distance a writer finds between their work and the natural inclination of a general audience to read it. Besides “sinking into depression at your inability to make a difference in this cold world no matter how hard you try,” there are two ways to deal with this. One is simply to accept that you occupy a niche, and be happy about it. This can be a perfectly comfortable and indeed honorable way to spend a career. You write for the people who care about the stuff you write about, and don’t worry about every else. Makes a lot of sense. There are tons of reporters out there that you and I may have never heard of but who are treated like gods at the annual Ball Bearing Manufacturing Conference and Trade Show. This is fine.

For those who aspire to reach a mainstream audience, though, this will not do. If you write for general interest publications rather than small trade magazines, you are obligated to do what you can to draw The Average Reader into your story no matter how minute the population of natural enthusiasts for the topic may be. Beyond that, most writers believe that the stuff we write about actually is important. Why else would we spend all this damn time on it, instead of doing more lucrative things like buying bitcoin, or working at the post office? All the reporters writing all these deep dives on climate tech and the bond market and fast fashion and One Weird Guy’s Crazy Life really want you to read the stories, for (mostly) noble reasons. A large percentage of the breathless promotional language and falsely dramatic ledes and weird story structures that leap back and forth and time are just clumsy, endearing attempts to get you—You!—to pay attention. I hope that you know that you are wanted.

Let me talk about labor reporting in this context. First of all, I have always rejected the view that labor is a niche beat. It’s about work. You know who works? Almost fucking everybody! Furthermore, every newspaper for the past century has had a Business Section. “Business” is treated as one of the staple beats of journalism. Labor is the business beat from the perspective of human beings rather than capital. Very few of you are likely to become CEOs or hedge fund millionaires, but almost all of you are part of labor. It would make more sense if publications had standing Labor sections, and then had a few specialized reporters who talked to the corporate executives, in the same way that some hardy reporters specialize in visiting prisons to chat with serial killers. I will not continue down this road because it will go on for five thousand words and end in a lot of tedious ranting. Suffice it to say that labor reporting is directly relevant to the lives of most people.

Despite this, labor reporting in the mainstream press is relatively rare, especially compared to coverage of the same issues from the direction of Business or Politics. The number of full time labor reporters employed at mainstream media outlets today is probably fewer than the number of your fingers. Most good labor reporters are either employed by small outlets, or are freelancers. The upsurge of labor coverage that accompanied the past decade’s unionization of the media industry itself is now coming to an end, as layoffs sweep many of the publications that unionized.

The material outlook is a little grim. (Positive mental attitude!) No matter what happens to the supply of labor journalists, though, we all are faced with the challenge of make you want to read our stuff. A certain slice of labor journalism—especially stories about bad behavior by well known companies like Amazon or Starbucks—does tend to find a mainstream audience. But the deeper you go into the actual functioning of organized labor, or the travails of industries that are not as sexy or well known, the more the general audience fades away. This is bad not just because we all want an audience, but because of the fact that labor journalism is important to the very people who are not reading it.

Most people who are not union members feel remote from the labor movement. They have a hard time believing that the machinations of organized labor somewhere far away from them matters to them. The trick is to draw the line from the life of a regular person—You!—to the labor movement. There are many ways to do this. One effective method is:

You have a job—> Your job sucks—> Imagine if your job could be better—> That’s what unions do—> Let me tell you about it.

This method can reach just about anyone, on a very personal level. I also like to use a more politically focused argument that I think is central to the reason why everyone should care about the labor movement and its power:

America sure is fucked up today—> Why?—> 50 years of rising inequality—> How the hell do we fix that?—> Give working people the power to take back their fair share of the money—> Unions.

This, at much greater length, is the central argument of my book, which I hope that you will buy and read. You can add specificity to this argument also, depending on what issue people currently feel frantic about. Here is a timely version:

Trump—> Fascist strongmen like him rise when people lose faith in the American dream—> The American dream died due to 50 years of the rich getting richer while wages stagnated for the working class—> That happened because of the decline of worker power—> That happened because of the decline of union density—> How do we bring it back?

Or:

AI—> That’s gonna eat your job as a (checkout clerk or lawyer or truck driver or teacher or etc.)—> How do we protect ourselves against its unchecked advance?—> The government won’t do it—> Worker power is the only protection—> Unions.

You get the point. These are all methods of just putting emphasis on different parts of the same argument: That even if you do not think of yourself as a part of the labor movement today, what the labor movement does or does not do is important and relevant to your life, because it is the very best tool to fix the underlying ways that America is broken. So when you see an In These Times feature story about a group of reformers based in Seattle who want to unseat the leadership of the UFCW and unleash a new wave of organizing in the grocery and health care and cannabis industries, do not think to yourself, “What does that have to do with me?” Think, instead:

I don’t make the money I deserve—> Because my boss has too much power and I have too little—> Because of a regime of corporate-friendly regulations and laws that have arisen over the course of decades—> Because the power of labor to defeat such laws has been declining for 60 years—> To turn that around we need to revive unions—> That means unions need to organize millions of new workers—> That means the biggest unions in America must lead the way on organizing—> UFCW is one of the biggest private sector unions—> But they’re not doing what they could and should be doing—> We need to fix that in order to tap their potential—> But how?—> Read all about it.

I didn’t say it was pithy. But it’s true. Once you understand the potential of the labor movement to fix the things that are fucked up about your life, and about the entire country, it is easy to get excited about it. And I hope you will.

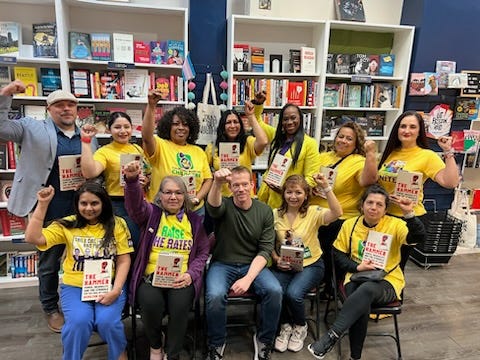

Also: Support the Labor Movement Book Tour

My new book “The Hammer” is about all of this stuff but with a lot more very interesting reporting all over the country. You may find it of interest. I am also getting a chance to talk about these things to cool people all over the country on my book tour. It’s really great. Here are my upcoming book events in April—including events TONIGHT and TOMORROW in the Bay! Come out and see me if I’m in your area, seriously.

Thursday, April 11: Oakland, CA—At the Oaklandia Cafe x Bakery, 5 PM. In conversation with Eli Rosenberg. Event link here.

Friday, April 12: San Francisco, CA—At the San Francisco State U Student Center, with DSA SF Labor. Event link here.

Monday, April 15: Los Angeles, CA—At Stories LA, 7 pm. In conversation with Adam Conover. Event link here.

Sunday, April 21: Chicago, IL— “The Hammer” book event and Labor Notes Conference after party at In These Times HQ, 2040 N. Milwaukee Ave. 5 pm. Get your free ticket here.

April 23: St. Paul, MN—At the East Side Freedom Library, 7 pm. Event link here.

Thank you for reading How Things Work. This site is straight up independent media. It exists only with the support of people like you who choose to pay for it. Paid subscribers allow me to pay the bills and keep this site free to read for everyone. If you can afford it (and it’s cheap!), think about becoming a paid subscriber today. Our cause is solid.

Now, before admonishing me, hear me out.

I ain't saying that smoking is good for you, the dangers are well known, and as a smoker I fully agree it's a bad, bad habit.

But.

Nobody cares about your health really, and if you doubt it just take a look at the food they feed you, the poisons and the pollution everywhere, and the general quality of life low income people (and not only) have come to expect.

What's this got to do with unions, you say?

Bear with me.

Before smoking was vilified, and while it was socially acceptable, workers who smoked (and that would be the majority) always demanded their break.

No way you can make smokers work longer than they have to, without a "smoko".

During the break, their hands busy rolling, smoking, lighting a cigarette, offering their lighter, they'd socialise with each other, and what would random workers talk about?

You guessed it!

Work, the boss, payment and whatever else they had in common.

Kaboom!

Here's your union in the making.

Fast forward to today.

I was passing by a construction site the other day, and workers were having their lunch break. Nobody smoked, naturally. The outcast smokers, (that is, one guy maybe), were far from the crowd, as the law demands, looking around with a guilty face. The majority of the workers were all sitting on a line, stuck on their phones, totally oblivious to the world around them.

Now try getting a Union out of these guys.

Conclusion? The war on smoking has always been part of the class war, but smartphones and social media were the final nail in the coffin of unionisation.

Can we undo this?

You could try taking $ bets on the outcomes of reform efforts... Also, why aren't there more mystery/detective novels starring a health and safety rep, or a union steward? Life and death stuff, full of tension, swarming with enemies. See Tim Sheard's Lenny Moss novels -- I assume everyone is familiar with them!!!