Ride or Die, Cowboy

Life is cheap at the Houston Rodeo.

“Lippy broke down and cried a time or two, thinking of Gus. To him, the mysterious part was why Gus wanted to be taken to Texas.

‘All that way to Texas,’ Lippy kept saying. ‘He must have been drunk.’ …

‘Why Texas beats me,’ Soupy said. ‘I always heard he was from Tennessee.’

‘I wonder what he’d have to say about being dead,’ Needle said. ‘Gus always had something to say about everything.’”

- “Lonesome Dove,” by Larry McMurtry

Larry McMurtry’s irascible literary cowboys, at home on the dirt of the open range, would not have known what to make of modern Houston. Neither do I. It is a city that shields its face. Trees everywhere, but also cars. Highways that rise so high it feels like you are driving a helicopter. The buildings seem incidental to the roads, not the other way around. The kind of place that would have a parking lot for a parking lot, and a corn dog wrapped in a corn dog. The city’s lack of zoning means that anything might be located anywhere. Power plants next to parking garages. New hotels next to abandoned lots. Low rises next to skyscrapers. It’s interesting, since you never know what you will find when you turn a corner—Art museum? Auto scrapyard? Adventures abound—but it makes it very hard to come up with any unifying aesthetic, or even a sense of style. What the fuck is this place about?

Perhaps it is still about cowboys. Despite the urban sprawl and encroachment of air conditioned modernity, the most deeply rooted cultural institution in this city is the Houston Rodeo—the biggest rodeo in America, going stronger than ever in its 93rd year. Perhaps this is where the heart of it all lies: the heart of Texas, and by extension the heart of the part of America that is allowed to represent itself as the heartland. Perhaps, in tumultuous times, we are meant to return to the roots of it all, to ground ourselves in tradition, to exhale our momentary strife and breathe in the air of our origins.

Sawdust and cow shit. That’s what the air of our origins smells like. It struck you as soon as you walked into the enormous NRG Center where the Livestock Show portion of the rodeo was being held, overpowering the industrial HVAC system. There were long rows of stalls, each holding one or two nice looking head of cattle, which I am going to call “cows” here for ease of expression. And next to the cows in each stall was a farm family—mom, dad, kids—all sitting in those folding canvas camping chairs, looking bored. The best way to make money in livestock would be to sell those camping chairs. They were ubiquitous.

Spectators could walk right down the rows and look at all the shiny coats of the cows. Mostly the ass part, which was generally pointed out towards the walkway. I immediately stepped in cow shit. “Don’t wear your fresh new Puma high tops to the livestock show,” is one insider tip I can offer to those of you who have never been. After this I understood the existence of cowboy boots, which I had previously regarded as unfashionable. Employees, who all seemed to be Latinos and who wore neon orange vests reading “LABOR QUICK” and who were doubtless prime examples of the social costs of outsourcing jobs to avoid labor regulations, pushed plastic shovels up and down the rows, all day, scooping up the fresh shit that had fallen in the past ten minutes. Not quick enough to spare me, though.

The cows seemed to mostly be tended by the children. It is kind of a shocking sight to see thousand pounds cows being led around by kids who weigh less than a tenth their weight, but centuries of breeding out aggression have made this possible. When it was time for the actual “show” portion of the livestock show, the kids all led their cows into a big arena the size of a football field and they all sort of stood in a line, like the Westminster dog show of cattle, and men wearing suit jackets and cowboy hats came around and looked to see which cow was best. This examination involved rubbing their hands over the cow’s shiny, groomed haunches. “Now that’s a smooth cow,” I imagine the judges saying to themselves. Then they declared a winner. (I am sure there are loads of nuance to this, a world of knowledge of animal husbandry, a proud tradition of cattle raising that is every bit as valuable as any other field of study, and I encourage all of you to study it at your leisure, but I will not be providing it here.) The cows themselves went along with this charade, being pushed and pulled around by ropes in front of a crowd of humans for no apparent purpose. They expressed their displeasure only by periodically declaring “HRRRRMMMMM,” which is cow for “Get off my face, man!” The emotion that cows most embody is “resigned acceptance,” which may account for their persistence. It is emotion that remains useful no matter how modern America gets.

The livestock show was a family event. Most of the men there, to my eye, looked pissed. This may be a matter of unfair projection—when I see stout men in cowboy hats I tend to think of police, which I categorize as “people who are just waiting for a chance to beat you up”—but there is also a genuine and omnipresent sense of restrained violence that sits just beneath the surface of any gathering of thousands of men who prize macho values. I attribute some of this to the fact that most of the farmer families contained a buxom young farm girl, and these girls were constantly at risk of being lured away from the farm and up to the big city by some sly predator who promises her a world where men don’t tuck their shirts into their jeans, and this omnipresent threat causes all of the dads of these girls to constantly be scanning the horizon for threats when they come to a crowded urban setting. I saw not an inkling of real violence at the rodeo—not a single fistfight. Everyone seemed very polite. But I could never get out of my mind the inherent possibility of ass kicking that comes with immersion in a world of cowboys. Guys who work on ranches for a living tend to be husky and strong in a way that exceeds people who live in cities and go to gyms, so I could not imagine winning the imaginary fights, either, which set me further on edge.

The Livestock Show building was full of vendors, which were stereotypical: Hats, leather goods, whiskey, beef jerky, barbecue, belt buckles. There were Ford trucks on display with grills that came up to my neck, and Chevrolets with grills that came up only to my breastbone, demonstrating why Ford is the more manly brand. There were scantily dressed booth girls in low cut tops selling not Ferraris, but Kawasaki MULE carts made for hauling on the ranch. Mattress Firm had a huge display of expensive beds, presumably because cowboys are a population with a high degree of orthopedic injuries.

Elsewhere there were displays meant to explain and, I dare say, glamorize farm life to impressionable children. The petting zoo was a chaotic swirl of children and goats, mixed together in a hurricane of “bahhh”s and backpacks. At the pony ride booth, a vacant-eyed attendant in an American flag-print shirt walked alongside the pony, endlessly trudging in a circle, a demonstration of the principle that the prison guards are just as much in prison as the prisoners. At the poultry display, the entire life cycle of chickens was illustrated by actual chickens. There was a big glass case holding dozens of eggs, all of which were in the process of hatching. You could stand there for a few minutes and see a trembling, bleary-eyed baby chick emerge from its shell, blinking at the harsh overhead lights of the convention center, wondering what sort of hell world they had entered. Among the eggs were a smattering of dead baby chickens, who were not strong enough to make it on the big stage. Life is cheap on the farm.

In a separate building, on the other side of the carnival with all of its funnel cake and fried Oreo and turkey leg vendors, there were horses. They were also large animals led around by children, but they seemed to display more athletic verve than the cows. Both pooped prodigiously. The horses trotted around on dirt, whereas the cows seemed satisfied to sit on turf. That is a key difference to look for if you are ever placed in the position of having to identify animals in the wild. There were handsome saddles for sale for $4,600. That is enough money to purchase a wheeled vehicle, raising the question of why one would spend it on a saddle. I do not know the answer, but I do know that—considering the cost of horses and cattle and big trucks and farm equipment—the idea that farmers are living a more humble lifestyle than their city counterparts is bullshit.

In the evening, inside the stadium where the Houston Texans play football, the real rodeo began. Cowboys on horseback rushed out and roped running calves by the neck and the feet; they leapt from horses onto calves and wrestled them to the ground; they rode bucking broncos and bulls, leaned all the way back across the angry animals’ backs, their hats somehow staying on their heads. This was the biggest rodeo in the world, the premier event of the pro rodeo circuit, and the prize for the top winner here was only $65k—less money than a mediocre relief pitcher for the Houston Astros makes for a single night’s work. The rodeo’s most vivid lessons are “don’t be a calf” and “don’t be a cowboy.” The prisoners and the prison guards of the West destroy one another’s bodies as industrial agriculture conglomerates chuckle.

You might expect the Houston Rodeo in 2025 to be freighted with a heavy dose of politics. Not so. In the entire day I spent there, the only hint of overt politics I saw was a single “GULF OF AMERICA, EST. 20205” t-shirt for sale at a single vendor. There were no Trump flags. There were only American flags. The people here were concerned with cattle and cowboys, with prize horses and chicken fried bacon. Let that be a comfort to you.

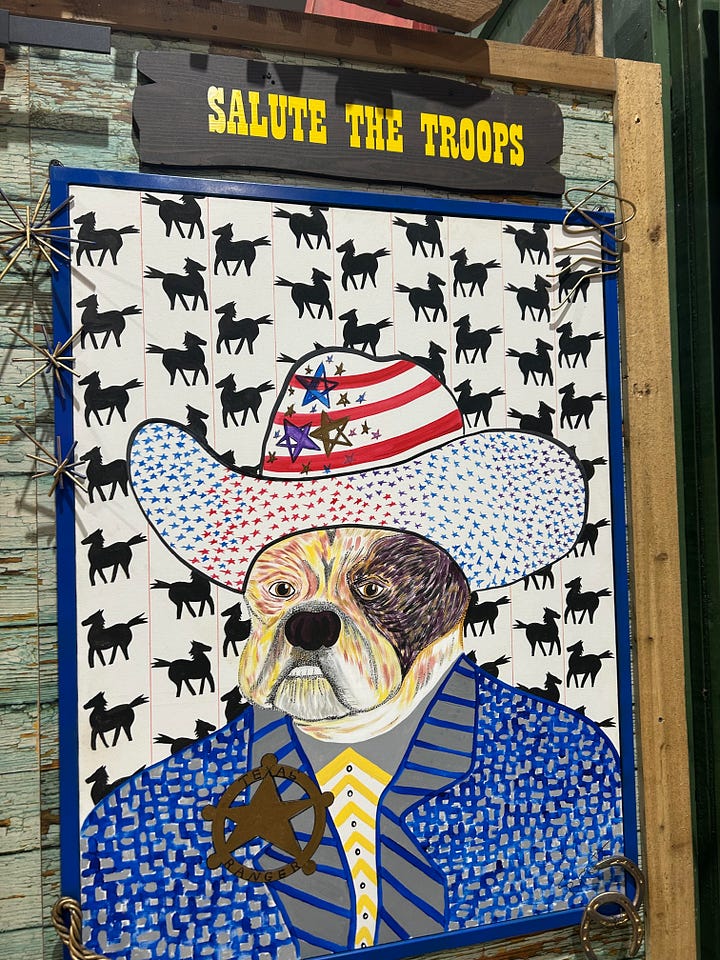

The rodeo was here before the president and it will be here after he, and the rest of us, are dead in the ground. It’s politics are not of the fleeting sort. They are the sort of politics that constitute an entire life in a place, where all of the most troublesome questions have answers that are so widely agreed upon that there is no need to discuss them. Before the rodeo started, a smiling, gap-toothed child recited the Pledge of Allegiance. There was the salute to a member of the military, which everyone rose and clapped for. And, as the national anthem played, there was a woman wearing red white and blue spangled spandex, standing high astride a horse draped in the same colors, holding an American flag proudly as she rode circles around the floor of the stadium. When the song reached “the home of the brave,” a fountain of sparks shot up from the top of here flagpole, and she sprinted at top speed back into the tunnel, a streak of patriotism trailing sparks. And then the lights went down and the overhead screens showed an image of fighter jets and the stadium’s sound system ROARED and the whole place rumbled with the sound of jet engines. And then rodeo champs Tuf Cooper and Richie Champion and Ryder Wright defied death. These are the sort of politics that spread so wide that if you are inside them, you wouldn’t even know what questions to ask.

Life is cheap. Baby chickens die. The cattle is slaughtered. Get shot in the military or kicked off a bull or swallowed in a grain silo. Live it up, while you can! Eat the fried Nutter Butters! Ride the bronco! Take on all comers! Any day can be your last.

It is not possible to roll into some city you have never been to and expect to understand everything about it. You can never know all of its history, its traditions, the relationships of the people there to one another that make up the real stuff of life. It is preposterous to even imagine that you could. All you can really do is walk around Houston, while the reflection of the sun off the glass buildings bakes you with heat rays, passing the sort of enormous boxy homes that prosperous dentists build to validate their life choices to themselves, and the sort of run down homes that have a remarkable number of old cars in the yard, and the big stretches of dusty dirt where the cows and horses live, and think about the question, “What would life here be like for me?” I have a hard time mustering affinity for the Texas lifestyle. Neither cars nor trucks nor horses appeal to me. There are women at the rodeo who walk around with challenging stares, in cowboy boots and short jean shorts and tattoos on their thighs and cut-off t-shirts reading “Save a Horse, Ride a Cowgirl,” who illustrate some of the allure of the lifestyle, yes, but in general the combination of American flags and Ford Super Duties in endless parking lots and heat wafting off industrial friers on a hot day would make me want to uproot my life and move to a different state. This failure of empathy is an affliction that does not serve a writer well. We must stretch our own imaginations enough to fit the lives that we feel least able to comprehend. Otherwise, we are just tourists.

Charley Crockett, the only country singer I like, played a show at the end of night, on a star-shaped stage that rolled out onto the middle of the stadium floor and rotated slowly in a circle so everyone would get an equal view. He sang,

“A one trick pony knows

That it’s all about the show

Life is but a rodeo

And you can write that down”

I wrote it down. In the seat next to me was a surly cowboy, who seemed displeased to be squeezed up against me all night. We had not spoken a word. But finally he turned to me.

“Who you writing for?” he asked. I told him.

“I love this guy,” I said.

“I love this guy too,” he said. He had had a few beers. “This is the best show in all the world.”

“I’ll come back,” I said.

“You gotta come back,” he said.

I nodded. He nodded back.

“Welcome to Texas.”

More

Previously, in dispatches: My Failed Attempt to Suck the Walmart-Flavored Blood of Real America; My Kasual Kountry Weekend With the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan; Hell Is Empty and All the Hedge Fund Managers Are at the Bellagio; Among the Junketeers: 90 Hours in Vegas, Selling Out Hard; Cuba Welcomes You, Yankee Imperialists!

Thank you for reading How Things Work. This is an independent publication. It does not have advertisers. It does not have corporate funders. It does not have a paywall. It is an experiment in media funded directly by you, the readers. We have been going for a year and a half now with nothing but the support of readers just like you who choose to become paid subscribers, because they want to. I think this is a good model and I hope it continues to work. If you want to help this place exist—and help keep it free for everyone to read, regardless of income—take a quick second right now and become a paid subscriber yourself. It’s not too expensive and it is good karma. I appreciate you all for being here.

Man, I can smell this article. Great work brother.

I moved to the Houston suburbs from Philadelphia three years ago for a marriage that ended up not working out. If it wasn't for our children, I would have been on the literal first plane back to Philadelphia after the marriage ended. I simply do not belong here in any capacity. That's the most generous way I can put it. I do not begrudge anyone who wants to live here (cheap houses! Great BBQ! H-E-B!), but I can't see a way I will ever belong in a place with book bans, everyone telling me to have a "blessed day," endless elaborate Punisher/Blue Lives Matter-mashup truck decals, the looming threat of a natural disaster at any point, and people who longingly embrace the cultural low-point of an event you laid out above.

I don't really have a positive spin to end with here. I'm...stuck. Therapy helps.