Private Equity Vampires Suck

Megan Greenwell discusses her new book, "Bad Company"

Six years ago, Megan Greenwell was ensconced in a fulfilling job as the editor of the popular sports and culture site Deadspin. Then, a private equity firm bought the company. What followed was one of the modern era’s most excruciating demonstrations of finance guys fumbling their way to a media industry disaster via incompetent meddling. Greenwell quit, followed shortly thereafter by the rest of Deadspin’s staff. (The politics site where I had been working, Splinter, was shut down by the same clowns shortly before the Deadspin exodus.)

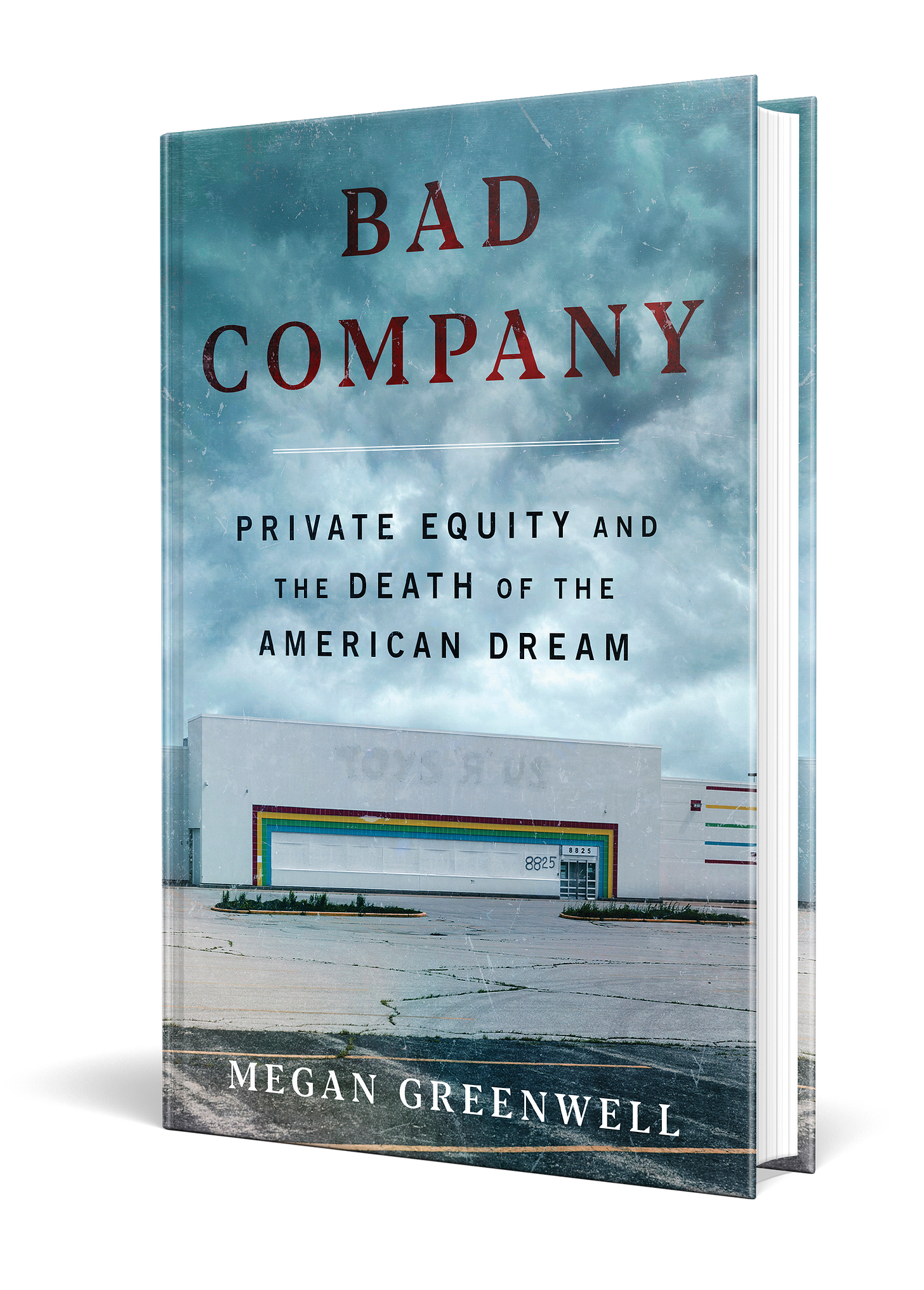

Greenwell’s journalism career was fine. And the experience opened her eyes to the predations of private equity on American workers—not just in media, but everywhere. Next week, her deeply reported new book “Bad Company: Private Equity and the Death of the American Dream” will be published by HarperCollins. I spoke to Megan about what she’s learned about the bloodsucking industry that is coming for all of us, and what we can do about it.

How Things Work: When you resigned as the editor of Deadspin in 2019 you wrote one of the all time great Gawker Media posts, "The Adults in the Room," about how the allegedly smart private equity guys who took over our company didn't really know what they were doing. How did that experience plant the seed for this book?

Megan Greenwell: I wrote that blog basically in a fugue state, to be honest. I was completely devastated to be leaving my job, but I knew there was no way I could stay, so I started writing stuff mostly so that I didn’t forget it. I wasn’t even really sure if I was writing a blog or a journal entry, until Barry read it and said we’d be publishing it. I knew essentially nothing about how private equity worked except insofar as it had blown up my own life.

When my agent emailed me one line about the piece — “This is a boookkkkk.” — I resisted at first. I don’t like writing about my own experience; I’m a reporter. And although “The Adults in the Room” had gone upsettingly viral, I didn’t think anyone would care enough about private equity ruining sports blogs to pay $30 to read about it. But I couldn’t get private equity out of my brain. I started reading about how it worked in retail, hospitals, housing, and maybe a dozen other industries. And I realized there were almost no books out there that applied a narrative approach to private equity. After ghosting her for weeks as I went deeper and deeper down my rabbit hole of SEC filings, I called my agent back and suggested that maybe the book was not a memoir or a media story, but Evicted for how private equity affects workers and communities: in-depth profiles of four people who had actually lived through this. So that’s what we pitched.

My own mental model of private equity has always been a vampire, sucking everything from a company and leaving a desiccated corpse. On the other hand, PE firms point out that in many cases they do in fact fix up businesses and sell them in, presumably, better shape than they got them. What's your preferred way of explaining PE to people who aren't that familiar with it?

Greenwell: People often use the term “vulture capital,” which I reject — vultures eat things that are already dead! I do like the vampire image; we nearly called the book Vampire Capital (though I’m glad we didn’t). But for the most part, I find that the most effective way to explain PE to people is to just give them a very literal, dispassionate 30-second tutorial on how it works. My target audience is people who have a vague sense the industry causes problems, but don’t know even the very basics of how (which is by design! Private equity doesn’t want people to know!).

The elevator pitch is that PE bundles money from outside investors — university endowments, public pension funds, state- owned investment funds, ultrawealthy individuals, etc. — and uses that money to buy companies. But! Even all that outside capital makes up the minority of the total cost of any given deal. The majority comes from bank loans. And those loans are taken out not in the name of the private equity firm, but that of the company being acquired. Even though the firm is the company’s sole owner, even though its executives are the ones who decided to take out the loans, it is not legally responsible for paying the money back. Imagine I want to buy How Things Work, so I borrow one million dollars to buy hamiltonnolan.com. But as far as the lenders are concerned, I’m not actually the borrower, the guy who’s name is on the website is. Now I’ve insulated myself from risk, because you’re paying me a management fee to run your site, and even if I drive it into the ground, I’m not on the hook for paying back that one million dollars. You are. :)

You profile four workers in four different industries who have been subjected to the predations of private equity firms. One of them is a rural doctor who worked for a small hospital that was acquired by private equity. After reporting this book, do you think that health care and PE are just fundamentally incompatible?

Greenwell: Yes.

Oh sorry, do you want more than one word? There are huge underlying challenges when it comes to making money off of hospitals, especially rural hospitals. In an ideal world, we’d have a reckoning over why we have a system that requires rural hospitals to make money, but that’s a different conversation. But in the world in which we live, private equity is by many measures worse at making money off of rural hospitals — except for themselves, that is. And its patient outcomes are worse too. Part of the reason I was particularly interested in this community in Wyoming is that it’s a deeply Republican place; these folks are absolutely not marching in the streets for Medicare for All, they just think they should be able to have a hospital. And, without giving the end of the book away, I will say that their story ultimately offers a lot of reason for hope.

Another worker you profile is a journalist who (like us) saw her publication acquired by a PE firm. UGH. In fairness to PE scumbags, though, the media industry had serious problems even before they got here. To what extent do you think PE's investor-fueled layoffs are a driving factor of the journalism industry's decline, versus other causes like "Google and Facebook took all our money?"

Greenwell: Oh man, I love this question. I strongly believe that the mainstream narrative about private equity in industries like media actually undermines critics’ argument precisely because it blames them for too much! The whole first section of my book, which is called “Before,” looks at how the retail, media, health care, and housing industries essentially ushered PE in the door with decades of terrible decisions.

I was a baby journalist a thousand years ago when most local news websites were still pretty new, and nobody in charge saw a problem with making all their stories free online yet expecting people to continue paying for a print subscription. Decades before that, newspapers would have what were sometimes called “Penny Wars,” where they would lose money on each subscription just so they could boast they had more subscribers than their rivals. A lot of morons have run this industry, and it’s easier to blame PE or Facebook than to actually come to terms with their own failings.

Yes, and: Private equity itself has been unimaginably destructive to local media. In part because PE firms don’t actually give a shit about newspapers, in part because improving a business model is hard, slow work that doesn’t fit PE timelines, and in part because the debt they take out in newspapers’ names is so crippling, they very rarely seem to do any work to try to strengthen these publications. Instead of developing new monetizable products or trying to serve new audiences or really giving people any reason to subscribe, they simply cut and cut and cut some more. That further wrecks the newspapers’ business model, obviously, but the firms make their management fees and bonuses anyway.

Failure to properly regulate private equity is a bipartisan issue--we all remember Joe Biden giving private equity titan David Rubenstein the Presidential Medal of Freedom just a few months ago. What would you like to see the government do in terms of PE regulation, and what do you think the realistic political prospects are?

Greenwell: I do enjoy horrifying people with the statistic that 88 percent of all elected members of the House and Senate took campaign donations from private equity in the 2020 cycle, or the fun fact that in 2022 the top four recipients by dollar amount were all Democrats, led by Chuck Schumer. So yes, this is absolutely a bipartisan problem.

I felt strongly about not offering policy prescriptions in my book, not out of some sense of objectivity, but because I wanted to let my reporting speak for itself. I also don’t pretend to know what the right answer is! On one end of the spectrum, there’s Elizabeth Warren’s Stop Wall Street Looting Act, which would end the private equity industry as we know it by imposing stiff taxes on PE monitoring firms and requiring them to share responsibility for the loans they take out. Without unimaginably fundamental changes to the composition of Congress, that’s not going to happen.

There are some less-extreme-but-still-meaningful pieces of legislation that do feel within the realm of the imagination, though. President Trump has said repeatedly that he wants to close the carried interest loophole, which allows private equity firms to dramatically lower the tax rates on their profits. That idea has never made it through Congress, but I think there’s some chance this is the year: at least some Republicans who hate the idea of closing the loophole will probably fall in line so as not to defy Trump.

And there’s a lot happening on the state level. After the disastrous bankruptcy at Steward Health Care, a formerly private equity-owned chain of hospitals based in Massachusetts, the state legislature passed a bill with all sorts of new regulations for PE-owned health care companies. That’s just one state, and it’s not going to wipe out the concept of private-equity hospitals even in Massachusetts, but it does speak to what can be done at levels beneath that of Capitol Hill.

Millions of workers across America will at some point find themselves in the same position as the four people profiled in your book: Waking up one day to find that their new boss is a faraway, inhuman, and remarkably cutthroat private equity firm that cares nothing for them as employees or as people. What is your advice to workers who are suffering under PE ownership? How can they fight back?

Greenwell: When I was formulating this book idea, the thing I struggled with most was what the final section would be. I did not want to write 300-plus pages where the takeaway was “Everything sucks, bye!”, as tempting as it was. As a result, I chose protagonists who all had fought back in some way. One lobbied in front of pension boards across the country until she and her former colleagues shamed the private-equity firms that had laid them off into giving them something akin to severance. One went head-to-head with her landlord, at great personal cost to herself, just to try to protect her neighbors. One found a place for herself in a new sector of media, helping to pioneer a new and PE-proof business model. One, a doctor in rural Wyoming, went further than anyone would have thought possible, winning a truly remarkable victory for his community that I will not spoil because it’s my favorite reveal in the book.

This is a wide range of actions, which is the point. There is no one silver bullet to the private equity problem. There’s not even one solution in each individual industry: what works in one place, or in one company, may not in another. The good thing about that is that the workers themselves will likely know best what the right answer(s) is for their particular situation. And if they don’t know, there are all sorts of people who have been in their shoes to whom they can turn for help. The key, I think, is that nothing will ever happen without a couple of people — even, or perhaps especially, people who initially have no idea how to fight back effectively — taking a stand. As cheesy as it is to say, I do think the book shows pretty clearly that ordinary people truly can make a meaningful impact at the level of one company or one community.

More

You can preorder “Bad Company” from an independent bookstore right here, and here you can find a list of Megan Greenwell’s book tour events. Go see her! She’s cool. The Deadspin staff that quit went on to form Defector, a site that I actually pay my own hard-earned money to subscribe to and sometimes write for. Megan, the former Deadspin editor, went on to write this extremely respectable book, and meanwhile the Defector people are just writing about ham. This is the sort of editorial diversity that private equity stole from us.

Previously, in How Things Work author interviews: Tom Scocca; Jeff Schuhrke; Eric Blanc; Stephanie Kelton.

In journalism’s “post-job” world, a dystopian landscape littered by the corpses of media companies and stalked by murderous PE firms, maintaining a publication like How Things Work requires me to be “entrepreneurial.” That means that I now must tell you that the only reason that this site that you are now reading exists is because readers just like you make the choice to become paid subscribers. The price is a mere six bucks a month, or sixty bucks a year. Your paid subscriptions enable me to do this work. I don’t get a salary any more! This is it! I have faith in you, and you have faith in me, and together we will move forward into a brighter media future. Thank you all for being here.

Surprise, surprise, a good solution to fighting against PE is people, individuals taking a stand and relentlessly demanding a change. No matter how you look at it, it always comes down to us, fighting back, in any way we can. Nothing will change otherwise.

Greenwell is very articulate and plainly explains PE, so even dummies like me can understand the basics.

For some reason I've long seen "Up in the Air" as a textbook example of corporate greed and insensitivity, and despite *not* being PE-specific (IIRC Clooney just plays a general corporate downsizer), the plot's nearly identical if you instead assume a PE firm acquired Clooney's character's company and demanded mass layoffs.

Point being: it shows off the devastating human side of being shitcanned for literally no reason other than boosting shareholder returns. (One I imagine isn't dissimilar in feel to being shitcanned from a federal agency by DOGE, but to boost tax cuts for billionaires.) Sadly, far too many people – the ones "cheering on" needless federal layoffs, based on an assumption of pretextual "bureaucratic bloat" (never mind there being no "fat" to cut in the reality-based world) – seem to be devoid of empathy with regards to either mass layoffs or mass deportations.

Finally, PE has about as much place in healthcare as RFK Jr.: both make it worse, not better, in nearly every way. (At least PE execs aren't anti-science.) But in general the industry needs to be far more heavily regulated, which of course is very unlikely to happen until at least 2029.