Keep On Looking for Those "Corporate Values," I'm Sure They'll Turn Up One Day

Companies are machines and must be treated as such.

As troubled times wrack the world, more and more citizens are turning to one source for moral guidance: big business. Companies of all types find themselves beset by demands to issue A Statement On Current Events. And they do. Google’s CEO is deeply saddened by what is happening over there. Amazon’s CEO is hoping that peace arrives as soon as possible. Anonymous sources tell business reporters that executives are “tying themselves in knots” over how to craft the perfect statement of concern, and which words are appropriate to navigate these fraught issues. Employees, customers, and stakeholders of all stripes, seized by outrage and sadness, want to know that these grand companies, these titans of commerce, will act for justice, in accordance with their deeply held Corporate Values.

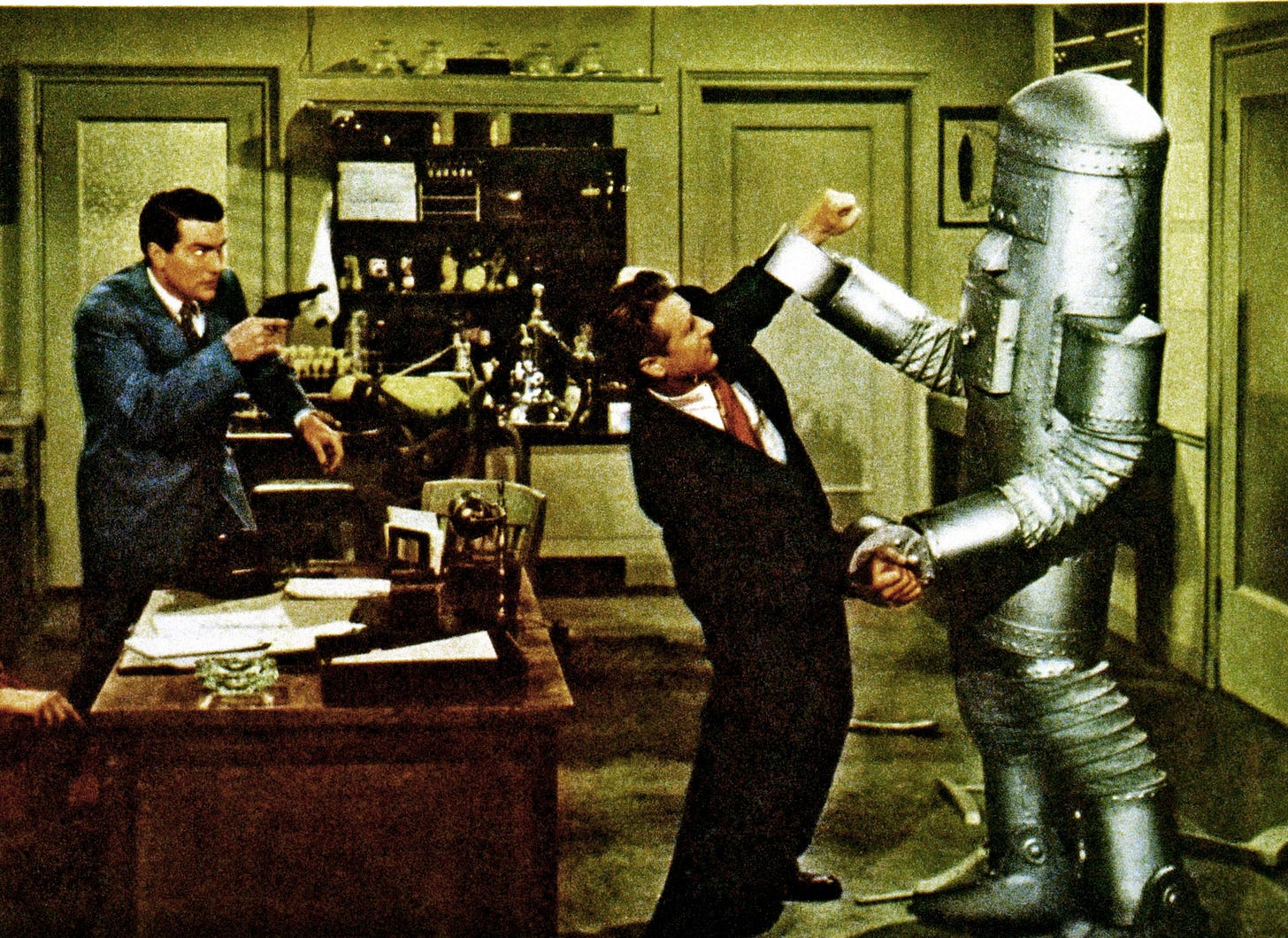

I have bad news, my friends: there is no such thing as Corporate Values. They do not exist. They are the Tooth Fairy of the business world. You may as well pick up the computer that you are reading this on, shake it around, and implore it to articulate a position on the crisis in Palestine. It might be able to show you a slide show of pretty pictures, and an encyclopedia’s worth of words, until you stop yelling at it. But inside, its heart is cold.

Companies are like computers for profit. They exist to make profits. All else is in service of that thing. They are not alive. They do not have feelings. They do not have beliefs; they have interests. (The interest is “to make profits.”) This is true of every company, from the grim cement factory to the most welcoming technology firm. A company is like one of those big, heavy, boxy computers, sitting on wheels. You may, if you like, gather a mighty force and put your shoulder to it and push it one direction or another. You may even shift the terrain beneath its wheels. But its response will be to roll just as far as it needs to settle back into a peaceful equilibrium, where it can continue its normal business operations. It can be moved, but it does not choose to move. It chooses only to make profits. Leave it alone, and it will reorganize the entire world in service of that.

“Branding” is the term for the eerie practice of humanizing the machines that are companies. A brand is a smiling face painted atop a computer’s cold metal skin. Brands can be useful for business—it is good for Apple that you think that it symbolizes creativity, and it is good for Johnson & Johnson if you associate with your family’s health—but like all murals, the brand can be scrubbed and redone if it loses its usefulness. It is simply a pacifying picture. Do not be lulled into believing that the mural on the side of the computer means that the computer is alive and you can talk to it and it is your friend. It is not. It is meant to keep you occupied while the computer whirs along within.

Some people find this analysis simplistic. “Companies are people,” they say. They will point out that different companies seem to do different things. They will point out that some companies put on progressive faces, and others lean into patriotic symbols. All of these things are true, and they are as meaningful as a few grains of sand strewn across a gigantic marble mountain. A small business, fully controlled by a single owner or a small group of people, may indeed choose to take political stances. It can put liberal slogans on its signs and put peace signs on the ice cream cartons and make donations to good causes. But with each level of growth—with each new round of investors—the ability of a company to be used as a personal toy degrades, and the demands that a company be run in service of profit increases. Financial abstraction is the enemy of human values. Ben and Jerry may have political beliefs, but eventually their company was bought by the Unilever corporation, whose shareholders are many of the world’s biggest money managers, who are investing the money of an entire universe of individuals and institutions who expect a single thing in return: profits. “Values,” apart from profit, are an alien term to hedge funds and private equity firms and to the Blackrock-esque oceans of capital that exist to deploy said capital in order to increase it. You can talk about values with your dog, and the dog may cock its head and look sympathetic, but it does not really understand what you are saying. So too with financiers. Values are not part of the language that they speak. They want FOOD.

By the time a company grows large enough to be part of the public markets, or to be controlled by titanic private investment firms, the pressure on that company to manage itself in service of those investors is so large as to be, practically speaking, the only thing possible. It is the ocean and the company is the fish. The fish may leap momentarily into the air, but it will be back. This is capitalism. A company is one node in a network of organized capital, one wheel in a machine that turns and turns for profit. Within this fundamental framework, companies have learned that there are stakeholders to be managed. They must have a brand and run ads to engage customers. They must have employee affinity groups and HR managers to keep employees sedate. They must have governmental affairs managers to befriend the politicians who might fuck with business, and they must have charismatic mid-level executives who can go speak to the community board meetings when it is necessary to get a project approved. But it is a mistake to interpret any of this behavior as a company exercising some set of moral or political or humane beliefs. These tasks are all necessary for the optimal functioning of the machine. The people whose job it is to make all of these corporate decisions are ultimately judged by how well those decisions optimize corporate performance. They are not judged philosophically, for christ’s sake. The boundaries of their own decisionmaking are tightly constrained. They may be nice and caring people but they will not decide tomorrow that the company is going to give all of its money to the homeless. Such a thing is not allowed because of how the machine operates. If you talk to corporate people about knotty political issues, you are sure to reach the point when they give the elaborate shrug. That shrug means: I would love to do something about these bad things, but of course we both know that that is not my job.

It may sound like I am letting companies off the hook here. It may sound as though I am excusing them from their amoral, psychotically self-interested nature. Not at all. This understanding of the nature of companies is precisely why I think they should all be chained up like prisoners in a dungeon. They are bad robots with no moral compass. They are empty machines programmed to make all of humanity work for their owners. What the United States has done—allowing companies to infiltrate its political system, acting as though companies are entities with “free speech” rights, granting companies life or death power over millions of working people who will plunge into poverty without them because there is no social safety net—is absolutely insane. Putting companies in the most powerful role in your society?? Man, that’s crazy! It is the very essence of companies, if you let them into the political sphere, to try to purchase all political power and use it exclusively to enrich themselves, with little care for who is harmed. That is what they do. That is how they are programmed. We know this. They are amoral machines of pure self-interest, and we, the fucking idiot children that we are, have been seduced into thinking that they are our friends, because of the friendly, painted-on faces. Giving corporate capitalism control of an electoral democracy is one of the most predictably awful decisions a nation could ever make. And we are all reaping its many grotesque rewards. For all of the sci-fi terror about what might happen if an evil AI ever got loose, there is little discussion of the fact that we are already living in such a world right here in the USA. Companies are very good at doing the specific things they do—making cars, producing food, churning out new drugs or computer programs or fashion designs. They should be allowed to do those things. And they should be locked in a prison of regulation to prevent them from doing anything else. To live in a world run by companies, rather than making them live in ours, is lunacy.

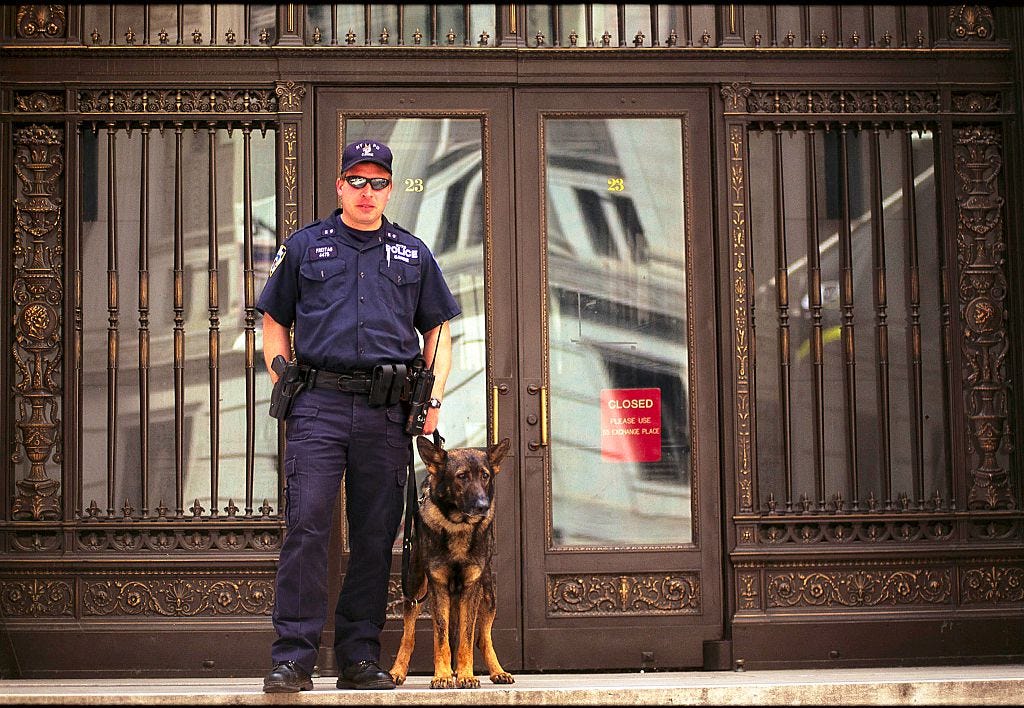

The only reason that I am typing this little rant at this moment is to try to gently reset the conversation around activism and big business. We do live in a world in which companies are powerful actors, so there is nothing wrong with trying to push them in certain directions for purely instrumental purposes. Yet all of this human activism should be designed with an understanding that we are dealing here with machines rather than people. Appeals to a corporation’s sense of fairness are a little farcical. Both sides of that discussion are playing out a little game that we all understand is not real. If you can bludgeon a company into doing something beneficial for the world by using the tool of bad PR, sure, go for it. But do not be mistaken about the mechanism at play. Machines have no sympathy. They respond to power, to force, in all of its forms. Deal with them as you would a hungry wolf that is always gazing at you to decide whether you are finally weak enough to attack.

This basic analysis—companies exist to make profits and nothing else, so expecting them to have values is foolish—may sound familiar from the Wall Street Journal variety of the political right. The key difference, though, is that those people argue that exempting companies from morality, and ceding to them the unfettered ability to perform their central function, will produce good outcomes for society. That is wrong, and absurd to anyone who has ever seen a community polluted by a strip mine or a Congressman in the pocket of a health insurance company. In reality, the contempt that activists often aim at companies themselves—unbreathing, mindless entities who cannot be shamed—can and should be aimed instead at the people who benefit from corporate power, and who work to arrange the world so that corporations can continue their dominance of it. They are a bunch of Renfields, ghoulish servants of Dracula willing to help him suck humanity’s blood in order to further their own gain. This is a small but important distinction. You cannot hurt Amazon’s feelings. You can, however, denounce Amazon’s CEO as a no good union busting cretin and spit in his sandwich if he comes into your restaurant. The machines can’t rule without their pathetic human allies. When the machines do evil things, is the allies who deserve the shame.

Also

The SAG-AFTRA strike is still going after 100 days. It is very, very important that their picket lines stay strong. Go join one. This is a good thing to do, right now. All the information you need is here.

The Hammer, my book about the labor movement and how it can save America and why it hasn’t yet, will be published in February. I have the galleys, and it looks cool. You can preorder it here, or wherever books are sold.

Thank you to the thousands of people who have subscribed to How Things Work. This site is able to exist because of paid subscribers who support it. Do you like reading this site? Kind of? Well, please consider very seriously becoming a paid subscriber, then. This is how we sustain a thing BEYOND THE MACHINES.

IIRC, SCOTUS decreed long ago that corporations rank above people. Probably true; they can kill will pollution and toxic, unhealthy foods. If we did that, it would be an illegal killing. They commit medical malpractice by reducing and eliminating health care availability while individual health care providers can be held liable. They buy politicians in a way we can’t (or enough of us try). And so on and so forth.

Preach. Corporate Statements aren't about values. They're about marketing and customer retention. Signaling a certain set of values is a way to attract a certain group of people (or to retain a broader, bland group of people). Corporate Statements are tools Capital uses for further capital accumulation.