Democracy and Power

Rotten things fall apart.

Humans developed voting as a method to use to decide things in lieu of killing each other. Democracy is a system in which each person has an equal share of voting power and therefore catering to the common good of the majority is the plainest path to electoral success. In theory. For democracy to be sustainable, each segment of society should have an amount of political power roughly proportionate to its own size. This fair relationship between individual power, collective power, and political power is what keeps a population bought into the idea of democracy. We know that our preferred candidates will not win every election, but we also know that in the long run, the distribution of power in a democratic system will allow the needs of the majority of people to be represented. If people stop believing in this, then democracy itself no longer appears to be a good deal.

The fair distribution of power throughout society is a necessary ingredient to the preservation of democracy. Otherwise, what’s the point? If democracy subjects the majority of people to the long term control of political power by a small minority, why would the majority of people ever agree that democracy is doing its job? They would eventually lose faith in the system. Then—whether through sudden overthrow, or slow nihilistic abandonment—the democracy would wither.

America claims to value its democracy above all. Yet our failure to value the fair distribution of power throughout our society is bound to eat away at public faith in our democracy and, in time, cause it to crumble. The original sin, of course, was never sharing power equally in the first place—America’s ruling class has only been dragged closer to universal suffrage by centuries of mighty efforts from below, and the use of outright bans on certain types of people voting has not disappeared, but only morphed into slightly more sophisticated versions of voter suppression. Even as our body of law has grown more equal, the reality of the way that power is apportioned in our country has remained unequal. In fact, it has risen drastically over my lifetime. That is due to the fact that America has not protected its system of political power from its system of economic power. Instead we have created a nation in which political power can be purchased with money in a very straightforward way. This system awards political power not according to population, but according to wealth. Oligarchy has the same effect on the public belief in democracy as all other sorts of minority rule. It proves democracy’s claims to be a farce. It produces the exact sort of cynicism that polls tell us Americans feel regarding their government. The lack of faith in democracy resulting from the failure of democracy to provide equal access to power causes people to say “fuck this bullshit.” In a two party system, where the choices are only “continue with what is happening” or “change it,” it will naturally produce a series of swings back and forth between parties over time, as the public grasps for fundamental change that they never receive. Since the end of the Civil War, the only president who was able to buck this trend was FDR—the one who instituted the most fundamental reform in the distribution of economic power, the power that had created America’s original grotesque age of inequality.

Electoral strategists think of political power as something that comes from winning elections. This view, the one that dominates the political media, encourages us all to spend time obsessing over swing states and winning over small percentages of voters as the path to fixing America’s problems. It imagines politics as a series of chess-like moves and countermoves. It channels reform impulses and their accompanying funds into tactics that try to get one party or the other to limp over the line of a 50% vote share, tactics that will then be countered by the other party. It is a perspective that fails to create a rewarding relationship between regular people and politics for the same reason that playing chess inside of a burning house will eventually make you wonder why the board is on fire. It directs attention away from the main issue.

The most useful way to analyze the state of American democracy is not to focus on the unwieldy coalitions of the two political parties and their respective toeholds in Washington. It is, simply, to think about the distribution of power in our society. Is it fair? Do portions of our society have power that more or less represents how numerous they are? If not, democracy is in trouble. If money can buy political power and the distribution of money is highly unequal, the rich will have a hugely unequal share of power, and consequently our government will tend to serve the interests of the rich and their associate businesses instead of serving the interests of the majority of people, and that is exactly where America is today. The economic inequality crisis is the political crisis. Rather than thinking about why the last fifty years of Democratic or Republican administrations has produced a society that would vote for a deranged strongman, ask instead: What about a nation where the top tenth of people control most of the wealth and the bottom half of people control only six percent of the wealth would make that bottom half of the distribution believe that democracy “works?”

This is no novel insight. But it is easy to see that the mistake that many befuddled political analysts make as America’s political leadership become increasingly absurd is to think that democracy itself is the core value, rather than “what sort of lives democracy produces for most people.” The scary part of American politics right now is not “Donald Trump got elected.” It is that, as capitalism naturally produces inequality and nothing adequate is done to remedy this, fewer and fewer people in America have the means to exercise true political power. First the democracy gets hollow, and then, when it gets brittle enough, it falls apart.

The value in thinking about politics in terms of social power distribution is that it makes asking the right questions and finding the right solutions to our predicament much clearer. It is not about identifying the next perfect candidate who can charm those last few swing voters into voting for the party that has also allowed inequality to flourish for the past half century, just a little bit less. No. It is about saying: How do we distribute power throughout American society more equally? In a nation like ours, where there is high economic inequality and also a system in which wealth equals political power, there are two basic ways to make our representative democracy healthier. Either you sever the connection between money and politics, insulating elections from the influence of wealth; or, you distribute the wealth in your society more equally. Both would be nice. Both are worth working towards. In reality, achieving the first is an idealistic project that will take many lifetimes. The second, however, is something that we know how to do.

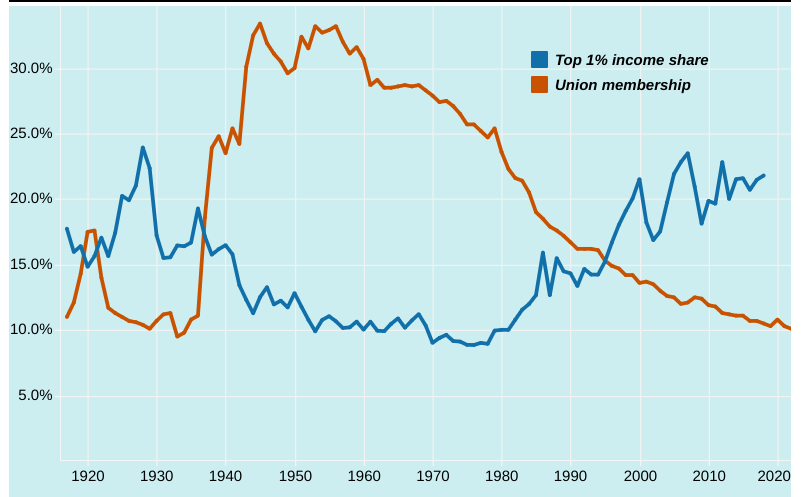

We know, from experience, that it is not enough to simply raise taxes on the rich and funnel some of that money to the poor, without changing anything else. (Wealthy interests will always be incentivized to recapture the government and shift the taxes and regulations back in their favor, which indeed is the story of post-WW2 America.) In order to reduce economic inequality for good and achieve a lasting redistribution of wealth, it is necessary to put power in the hands of the non-wealthy majority, power that they can use to protect the fairness of the system. Power in the form of lasting institutions that are self-supporting and do not rely on the rich for funding. What are these institutions, that allow the working class to pool and exercise its power, that can bend the curve of inequality back towards sanity, that create economic and political power for the majority, that can both redistribute wealth away from the bloated investment class, and protect that redistribution with its own electoral power? These institutions are labor unions. That is what they do. Strong organized labor and high rates of unionization create the economic equality and the political equality that lend long-term stability to a democracy. The decline of organized labor’s power in America since the 1950s has robbed the working class majority of its ability to protect its wealth and protect its political power and it has enabled the sharp post-Reagan rise in inequality that has led us to the point when a billionaire president is prepared to loot the government for his friends with the help of the world’s richest man.

This is why I write about organized labor so much. Unions are the only thing that do what needs to be done to fix America. Can you name another sort of institution that is capable of doing all of these things? No. (And reformist activism without lasting institutions has long failed to succeed. BLM was, numerically, the biggest protest movement in American history, yet just a few years later its policy goals have been rejected with great venom by most of the political power structure.) The broken power of organized labor has unleashed the ability of the rich to capture an insane portion of the nation’s wealth which has allowed them to purchase the electoral political system for their own benefit which has sapped public faith in our democracy which is producing increasingly demented and dangerous electoral outcomes. Either we continue down this path or we fix the poor distribution of power in our society that has led us down the path in the first place. Fixing the distribution of power means permanently taking away wealth and power from the rich and giving it to working people and giving them the means to protect it. That means strengthening organized labor. It is the load-bearing wall that has been eaten by the termites of capital for decades now. If we don’t fix it, the whole house will, sooner or later, come crashing down.

More

Related reading: On the need to make rich people participate in public systems; On the moral imperative to eradicate billionaires; On the redistribution of wealth; On the inherent power of labor.

My book, “The Hammer,” makes this case at length and with a lot of reporting about real people in the labor movement who are doing what needs to be done. If you are grasping for explanations of how we got to where we are, I think you would enjoy it. You can order it wherever books are sold. I will be in Baltimore, MD at Red Emma’s THIS THURSDAY, December 5, at 7 PM, talking about it with the great labor journalist Max Alvarez. Event link here. If you’re in the Baltimore area, come through.

This publication, How Things Work, is able to exist only because of readers just like you who choose to become paid subscribers. There are no ads here, no corporate donors, and no paywall. Only me and you and independent media. If you enjoy reading this site, take a quick second right now to become a paid subscriber. It is a small affordable action that helps to keep this place going. Thank you all for reading.

Great essay revealing fundamental dynamics of civic decay.

In the 1950's the CIA popularized the Gini Index (named after an Italian economist to describe the distribution of something among a population, where "0" means everyone has an equal amount and "1" indicates it is all concentrated in one person/unit's/country's hands) as a measure of a country's stability. They determined an index over 40 was a warning of civic unrest. For years the USA hovered unacceptably high at over 35 (close to Mexico) and far above the Scandinavian countries (e.g. Sweden is at 30 in 2024). Obama with his tax on stock transactions and the ACA was the only President since the 1960's to lower our Gini. Since then, especially with no raise in the minimum wage, impotent unions, the Republican minimization of estate taxes, caping income tax rates, and the Trump tax cutout, the USA Gini Index is now an estimated, unadjusted 48. One American is the richest man in the world. Three Americans have more wealth than the bottom 50% of the population. Beyond Musk's political power, both American families and American government have been starved, both economically and politically. You are quite right. For the last 50 years, and on an accelerating basis, we are watching, playing out in real time, civic dysfunction and disorder whose main engine is wealth inequality. OUCH! I agree, more than anything else this explains the panoramic dynamics of the MAGA movement. In the end the CIA was right, wealth inequality destabilizes a society. In the real world, each scenario will unravel in a unique way. Now, in real time, we are watching this great civic defect create its havoc.

"The most useful way to analyze the state of American democracy is not to focus on the unwieldy coalitions of the two political parties and their respective toeholds in Washington. It is, simply, to think about the distribution of power in our society. Is it fair? Do portions of our society have power that more or less represents how numerous they are?"

This resonated heavily with me. Too much of the conversation about politics in the US becomes immediately reduced to an electoral framework. Not only is it an unproductive framework to solely operate from, it also saps our ability to legitimately take stock of the material and social conditions laid out before us. As this article details quite well, the disproportionate accumulation of capitol, and by consequence, political power, has led us to a point where the only institutions capable of broad-sweeping change are the ones that are seemingly most compromised. If the majority of political discourse continuously hinges on incorporating these institutions without meaningfully reforming them, how can things ever change?

In my opinion, the resurrection of a more organized and militant labor movement seems to be this country's best shot at meaningfully reforming the economic conditions of society. One impactful step people can take is to spend more time thinking about the state of their lives and their neighbor's lives and question what they see. 'Why do I work so much? Is this normal? Are people receiving equal reward for equal effort? Why does my vote feel impotent? How does this change?' - In most cases you may find that the answer to these questions don't come from considering electoral strategies or party platforms.

Divided we beg, united we bargain!