Arts and Crafts

How things work, and why I'm here.

The way I always understood it was that a craft is something that you make with utility in mind: The carpenter makes a perfect chair. The chair’s value is that it can be used. Art is something that you make purely for self expression: the carpenter makes a sculpture that you can’t sit on at all, but looks cool and speaks to his eternal soul. It has infinite value for its creator’s eternal soul, and uncertain value for everyone else. A craft is done with an end user in mind, and can be judged by how well it meets the exact specifications of that user, but an art is done only to realize the vision of its creator, and can be judged only by the creator himself, in terms of how honestly it hews to his own creative spirit.

Clearly, journalism is a craft. Everyone will tell you it’s a craft. The owner of the publication will tell you what kind of stories they do there, and your editor will tell you how the story needs to be written, and the readers will tell you why the story sucks. We’re not writing poetry here, man. We don’t need your artistic vision; we need 850 words of inverted pyramid writing that clearly communicates the outcome of last night’s high school volleyball at approximately a sixth grade reading level. We need five thousand words of kind of macho flowery prose about a guy getting lost on a mountain that will appeal to the upper middle class readership of our men’s magazine. We need a two thousand word profile of the president’s new chief of staff that is flattering enough that he will take our publication’s calls in the future. The journalist is a craftsman who is expected to do what needs to be done. That is the job description. That is the business. If you want to write poetry, go be an unemployed guy who writes poetry.

Still, I’m going to tell you a secret: To me, journalism is an art. I don’t say this in some self-flattering way, to make myself sound deep. Quite the opposite! It is actually a view that most career journalists, including almost everyone who might be in the position of hiring people for journalism jobs, would consider to be juvenile. It’s the kind of romantic thing that should be drummed out of you by the reality of the business. Imagine being an editor who is responsible for putting out an entire magazine every week or month, juggling a dozen stories at a time, working long hours, and then you have one mopey bitch always muttering angrily when you change a single sentence. That mopey bitch is me. My basic belief has always been: Don’t fuck with my thing. If you have something to say, by all means, go write your own thing. But don’t mess with my thing. Yes, it is true that my writing is just as riddled with typos and needless run-on sentences and tenuous factual leaps meant to paper over laziness as anyone else’s. But it is mine.

It’s not quite that simple, of course. Big, fact-filled reported features are like skyscrapers, and even if the writer is the architect, you still need a building inspector to check it all out to make sure it doesn’t fall down. I think that deep down, though, all creative people have a dreamy side. The architect understands she can’t build a 100-story building shaped like an “S,” due to the laws of physics, but still secretly wants to. The journalist understands he can’t order readers to pause in the middle of a reported story in order to chew over a luxuriant thousand word riff about what the scene feels like, but… he kinda wants to put it in, anyhow. Journalism is creativity that is uncomfortably dressed up in a suit, for appearance’s sake.

This attitude is, to be clear, too precious. A little nauseating, even. Within professional journalism, this overly sentimental attachment to your own prose marks you as kind of stuck-up, difficult to work with, overconfident, a legend in your own mind (and no one else’s). The people who teach writing will try to whip this out of you. Editors will demand that you get over it or get the fuck gone. Readers will happily let you know that you are far too stupid to have such a deep-seated faith in your own ideas. Other writers, from poets to novelists to newsrooms, will proclaim the value of collaboration; they will gush about the drastic improvement that all this feedback brought to their work; they will pay glowing tribute to editors when they win awards, casting their own drafts as rough, dirty stones in need of polishing from these humble professionals. Successful writers will write books about how to write, and those books will advise against the stubborn, go-it-alone method. That is the first thing you need to get over, they will say. Their own success in the field is a testament to the wisdom of their words.

They’re right. Yeah. Still, this is how I feel: Don’t mess with my stuff. I don’t want you to tell me how to change my writing for the same reason that you wouldn’t go in and add a few brushstrokes to someone else’s painting: Not because it is perfect, but because it is mine. It is my expression of my own thought. You can express yourself in your own writing. But not in mine.

The trick is to maintain this hokey sort of purity while still earning a living. Everyone has a right to express themselves, straight to the poor house. Nobody will stop you from being one of those people who sits out in Union Square with a typewriter offering to write poems for $5. If you want to earn a living, though, you do what the people who sign the paychecks want. You do the craft. There is a long and barren road between “I want to be a writer” and “I now write successful books full of my own luxuriant musings and earn a healthy income from this noble life of the mind.” Journalism is where the creativity that writerly types yearn for meets an actual income.

And journalism, as a career, is for shit. Especially if you want to do the art–not a fancy art, just “writing what you want, and saying what you want.” Gawker, the only place that I have worked that actually allowed this sort of dynamic, was sued into bankruptcy by an angry billionaire, then sold to a big company that shut it down, precisely because it feared (perhaps with good reason!) what might happen if we all kept on writing what we want. I’ve worked for alt-weeklies, which were fun but had very little money; for left wing media, which is righteous but has very little money; and for a trade magazine, the most stable place of them all, and boring enough to murder your soul. I wrote for a momentarily well-funded politics site that was shut down by private equity owners who, I’m quite sure, had never read any of its stories. If they had, they would have shut it down faster. None of this is special. All of this is very much representative of what the median career in journalism today looks like. A small, lucky minority will catch on at some prestige place and flourish comfortably. Another chunk will never catch on anywhere, due to bad luck rather than lack of talent, and wash out bitterly. And the majority of us will float around like barnacles, resting for precious periods of stability before getting scraped off and sent floating once again, desperately freelancing and hoping the next resting place appears soon. We are, all of us, buffeted by big economic and technological and political forces almost completely out of our control, just like most other people, from the gas station to the classroom to the coal mine. This is one reason why most journalists tend to have a worldview that is inelegantly deemed “liberal,” and why those that don’t are usually rich or delusional or dumb. If you got laid off as often as we do, you’d be a socialist, too.

That is how things work. This is How Things Work. The ideal economic model for any writer is to be directly funded by readers. No investors, no advertisers, no bosses. Direct alignment of interests. Have you applied for a regular job lately? “Oh please, look at me! I promise that I really know how to do the thing I have been doing for the past 20 years! I’ll do anything to prove it to you!” It’s demeaning. I don’t want to sell myself, and also I’m bad at it. I want to write stuff. So I will do that here and see how it goes.

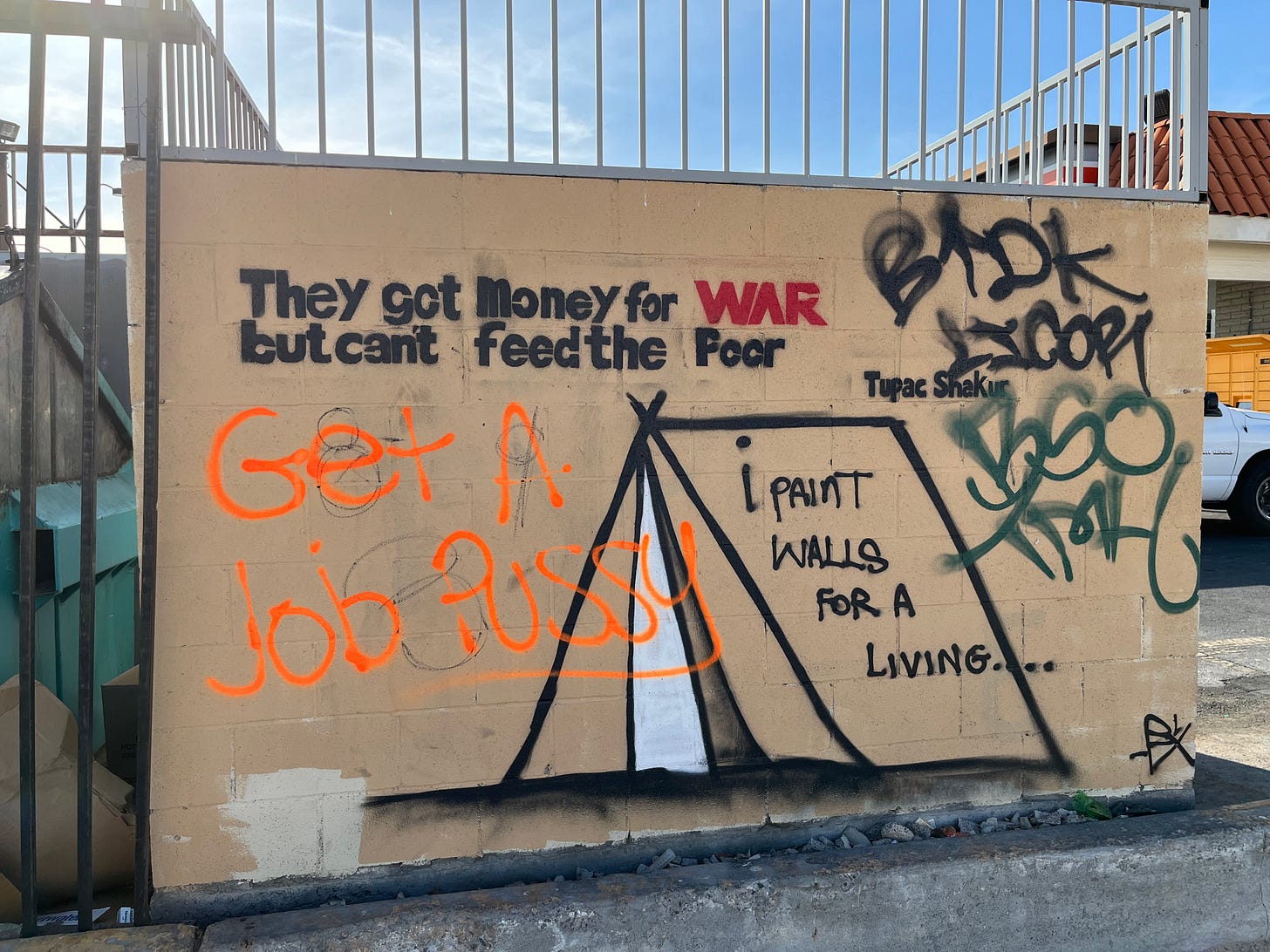

At Gawker, “How Things Work” was a tag that we applied to stories that tried to explain the underlying forces that produced the reality that we all see. Sometimes those forces are profound (capitalism) and sometimes they are very stupid (a single powerful celebrity petulantly asked for something, setting off a butterfly effect-like cascade of unpredictable events), but they are always interesting. My entire career in journalism has been produced by thinking about How Things Work. Basic things. Why do rich people run everything? Why do the rich get richer and the poor get poorer? Why are there all these homeless people? Why is there all this racism? Why is there all this inequality? Why doesn’t all this fucked up shit ever seem to get fixed? In recent years, I have written primarily about labor, and the many issues surrounding it. I have worked for years to try to help unionize my own industry, and I spent the past year writing a book about the labor movement, and how it can be better. But my interest in labor issues is not some inherent condition–it is the product of time spent wondering about the big questions above.

This is a good thing, I think, because you don’t need to be a nerd about labor or unions or politics or economics or anything else in order to enjoy the virtuosic prose and peerless insight that will appear on this blog. You just have to be interested in why stuff is how it is, and how to make it better. I plan to write about the things I have written about for years: Class war, politics, organized labor, and so on. I will write how I want, and say what I think. You can subscribe, and then I can make a living, and the whole system will run smoothly. It is unfortunate that there is no longer a stable media industry that can provide writers everywhere with middle class jobs that do not inevitably crumble into ruin–but on the bright side, there is now an unparalleled opportunity for readers to make me love them, by buying a subscription to this site. This model offers writers like me a dream job OR total failure.

We’ll see which. Either way, that’s how things work.

I had vowed not to subscribe to any more substacks but then I read this piece and felt moved to subscribe. Keep doing what you do.

Deep down I always knew you were an artist. Solidarity forever!