An Interview With a Journalist Who Has Been on Strike For More Than 500 Days

How the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette workers hold the line.

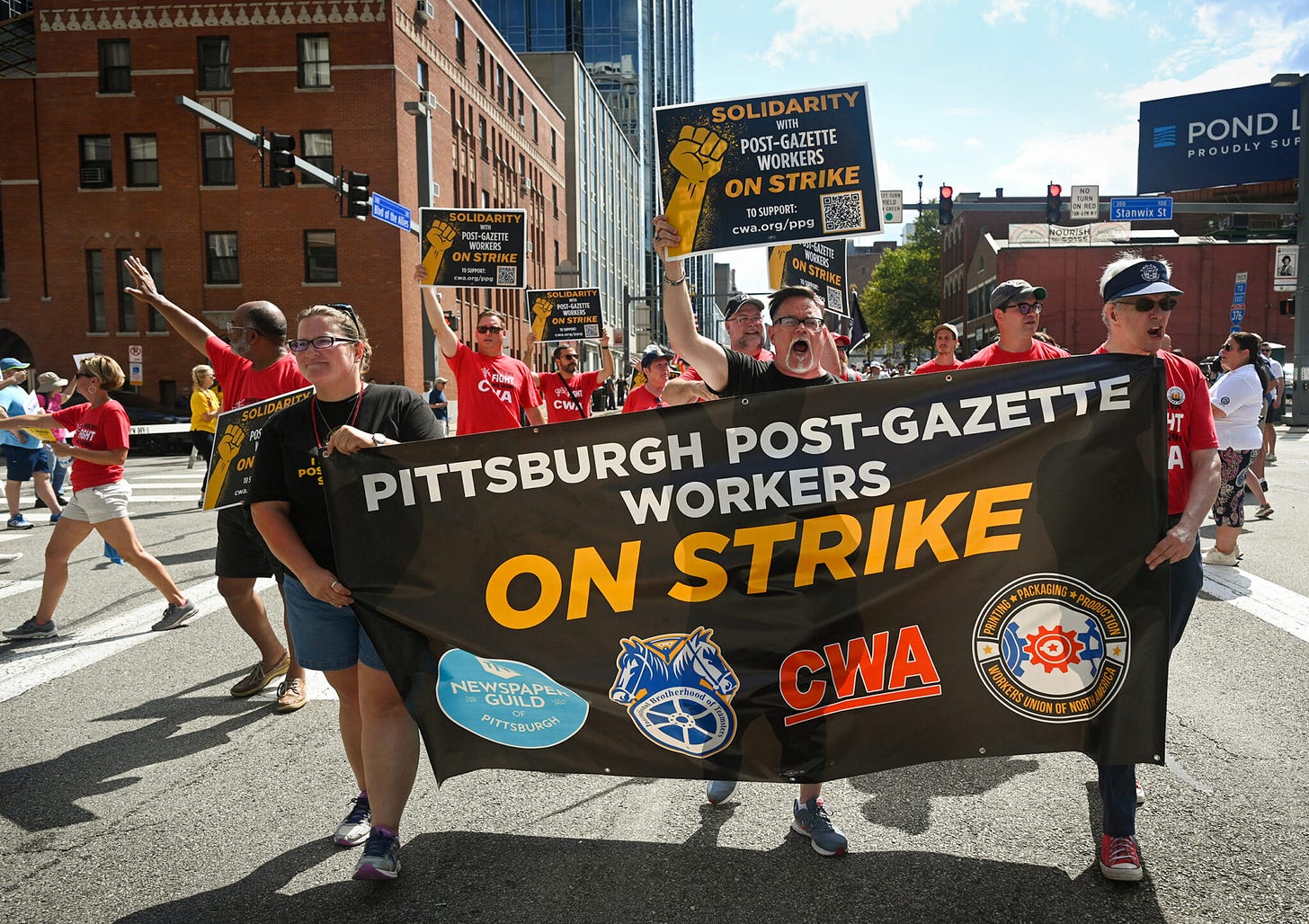

In October of 2022, the unionized newspaper workers at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette went on strike. First it was the production unions. Shortly afterwards, the journalists in the newsroom, who are members of the News Guild and who had been working without a contract for five years, walked out as well. Seventeen months later, they are still on strike.

A one-day strike is an act that requires great coordination and courage. A strike of more than 500 days is almost superhuman. The wealthy Block family, which owns the paper, has continued to operate it with a scab workforce. Yet the workers on strike continue to hold their line—starting their own strike paper in response, the Pittsburgh Union Progress. (Last November the union picketed the publisher’s wedding, one of my favorite strike tactics anywhere in recent years.)

It is easy for grueling strikes to recede from the public’s consciousness, even though their demands on the workers involved remain constant. How do these workers maintain their morale in such a long struggle? And what toll has it taken on them? To find out, I asked Emily Matthews, a photographer at the paper who is still on strike. Our conversation is below.

First, tell me about yourself: Why did you get into journalism? How long have you worked at the Pittsburgh PG? What were you working on there, and when you did you first go on strike?

Emily Matthews: I always had an interest in writing and photography and getting into journalism seemed like the best opportunity to have a career doing those things. I chose to focus on photojournalism because I was intrigued by how much of a story can be captured in one photo. You can look at a photo and instantly feel something that draws you into the story. Also, working in journalism is never boring. There are never two days that are exactly the same. I also appreciate getting to learn about what’s going on around me and sharing those stories with others.

I started working at the Post-Gazette as a two-year associate in Feb. 2020 and was hired on as a regular employee in Jan. 2022. I was taking photos of daily assignments ranging from food features to high school sports. I went on strike on October 18, 2022, which is the day newsroom workers represented by the Newspaper Guild of Pittsburgh joined the production unions on strike. Members of those four unions, which includes advertising workers, mailers, pressmen, and delivery drivers, went on strike on Oct. 6, 2022.

What were the key issues that prompted the strike? How much movement (or lack of movement) has there been on those issues over the course of strike? Why do you think management has been so intransigent so far?

Matthews: One key issue is health care. Members of the production unions had their health coverage terminated because the company refused to pay, and refused to allow the employees to pay, a $19 per employee per week increase in premiums. This led them to go on an unfair labor practice strike.

Members of the Newspaper Guild joined 12 days later in solidarity and also on their own unfair labor practice strike. Our collective bargaining agreement expired in 2017, and the company declared an impasse in negotiations and imposed conditions on us in 2020. We saw some movement in January of last year when an Administrative Law Judge with National Labor Relations Board ruled in our favor – the Post-Gazette had violated federal labor law by prematurely declaring an impasse in bargaining and unilaterally imposing conditions. He also ruled that the terms of the 2017 contract be restored until we negotiate a new one. This felt like a huge win, especially after being on strike for a few months with seemingly no movement. However, the company appealed the decision and hasn’t acted on the ruling at all. This led us to request injunctive relief from the NLRB, which would enforce the ALJ’s order to restore the terms of the old contract while we negotiate a new one. From what I understand, the NLRB is very understaffed and very busy, so we’re still waiting to hear back on that…

As far as bargaining goes, it is very frustrating. King & Ballow, the law firm that represents the company, doesn’t seem to want to work with us at all. We’ve brought concessions that they refuse to consider. They seem to be unwilling to budge or make changes from their imposed conditions. The King & Ballow lawyer spends the majority of the time writing or doodling on a notepad, avoiding eye contact, and answering questions with, “we like our proposal.” During one session, he seemed perplexed as to why management couldn’t do work usually reserved for union members or why we’re so adamant on having guaranteed work hours. It doesn’t help that there is no newsroom management representation at these sessions. Someone with the knowledge of how a newsroom operates could probably get things moving quicker. From what I’ve witnessed, this lawyer has a lack of understanding and an unwillingness to understand any of this from our perspective. I can only assume that this is what the company wants, since they’ve let it go on for so long.

It’s hard to know if the other unions’ bargaining sessions are any more productive. I know in the past, the unions proposed a health care plan, but the company refused to sign a participation agreement that the plan required. I think they have a session planned in the next week or so, so hopefully something comes of that.

I think the company isn’t doing more to end the strike because, so far, they have still been able to produce a paper – they’re still making money. They have scabs doing the work, and they’re still getting access to interviews and events to write about.

This has been an exceptionally long strike. How hard has it been on you financially, emotionally, mentally, and professionally? Tell me how you and your colleagues maintain your morale and your commitment to a strike that has carried on for so long.

Matthews: When the strike first started, I don’t think anyone could have fathomed it lasting this long. I was making about minimum wage at the Post-Gazette until Jan. 2022, when I went from being a two-year associate to a regular employee. From January to October, I was finally able to save up some money and my fiancé and I were thinking about finding a bigger place to live. That all stopped when the strike started. I think that’s probably the most difficult part about being on strike – knowing that it also negatively affects the people in my life. Even though my fiancé, family, and friends are all supportive, it’s still difficult. Beyond personal finances, I’ve just felt really hopeless and frustrated at times, especially more towards the early stages of the strike. I’m sure I’ve been miserable to be around, and I have even skipped out on gatherings with friends and family because I’ve felt so emotionally overwhelmed by the strike.

Several things have helped with that, though. We have a striker relief fund, where people can donate to help us with emergencies and necessities. That’s helped alleviate some anxiety around lofty unplanned bills like car repairs. We also have a sponsor a striker program where unions across the country can sponsor a striker. This helps not only financially but also emotionally. It’s nice to know there are other people out there thinking about us and offering words of encouragement.

We also started our own online publication called the Pittsburgh Union Progress (PUP for short). This helps tremendously because it gives us the opportunity to continue doing what we enjoy doing, while still being on strike. For better or worse, I feel like many journalists, myself included, have trouble separating our identities from our work. For me, the thought of not working at the beginning of the strike made me feel like I was losing a part of myself. Taking photos for the PUP, even if it’s just a couple assignments a week, helps me feel a sense of purpose and keeps me busy. Also, I’m definitely biased, but the PUP puts out a lot of good work! From coverage of the effects of the train derailment in East Palestine, Ohio, to features on local high school sports, the care and passion my fellow strikers put into their work is amazing and makes me proud to stand with them.

Also, the newsroom strikers have a Zoom meeting every morning Monday-Friday. During the meeting, representatives from different committees (that also meet separately) including health and welfare, actions, comms and community support, and bargaining and settlement will share any updates they have with the group. We usually end the meeting with announcements and, a recent addition to the agenda, dreams. The meetings give us the opportunity to organize events, discuss issues, and just generally talk to one another. There are also often several laughs shared which I think is okay, and even necessary, even though, and especially since, we’ve been on strike for 17 months.

The paper has been operating with a scab work force. Are you in communication at all with the journalists who are scabbing? For people in journalism who may never have given much thought to these issues, what would you say about the moral importance of respecting a picket line--particularly when journalism jobs are so scarce?

Matthews: I do sometimes see the scabs, especially when I’m on assignment for the Pittsburgh Union Progress, and will usually talk to them. I hope the strike ends soon and we can all work cordially with each other, but I wish they would learn and embrace the importance of being in a union, especially when you work in journalism. Most newspaper owners aren’t journalists, they’re business people. They will make decisions that benefit them but not necessarily ones that benefit their employees. If there’s nothing legally in place, why would they give you vacation, or sick leave, or health care, or a raise, or guaranteed work hours? The union and its contract guarantee all those things. And a union isn’t an abstract idea or one person making all the decisions. When you’re a part of a union, you have a say in your workplace. You can stand up for yourself and the work you do. When you cross a picket line, not only are you showing how much you don’t respect the strikers and their work, you’re also showing how you don’t respect yourself or your work. You’re sending a message to your employer that they can do whatever they want, and you’re not going to fight back or stand up for yourself.

Has this experience of being on strike changed you, personally or politically? What insights has it given you on the nature of labor movement, and on this industry?

Matthews: I do feel like being on strike has changed me. Before the strike, I was just happy to have a job in journalism. I didn’t fully understand how important it is to be in a union and how so many other newsrooms could be different if they were to unionize. It was very eye-opening to me how once the strike started, scabs started to get raises and the starting salaries for some of the new scabs were higher than what some of us were making before the strike. The company has racked up a ridiculous bill in legal fees since the beginning of the strike…but they can’t afford to pay a $19 increase in its employees’ health care? They couldn’t afford to hand out any raises for 20 years before the strike? It’s not right, and the company would continue to get away with it if we didn’t do something about it. The work that we do matters, and we deserve a contract that reflects that.

How can the public best support you all?

Matthews: Cancel your Post-Gazette subscription until the strike ends. Don’t share any of their links on social media or engage with anything they post. If the opportunity arises, don’t give them an interview. Subscribe to the Pittsburgh Union Progress here. You can also donate to the Pittsburgh Striker Fund, which helps us and our families with unexpected financial needs during the strike, here. Spread the word about the strike as much as possible. The more people who know about it, the better, and we appreciate any and all support!

Remember these journalists, every day. They are really extraordinary. And if you are in a position to hire people, I urge you to never hire anyone who has worked as a scab, ever.

More

—For months, a large group of people and foundations like the Economic Hardship Reporting Project have worked to put together an ambitious photo project on the American labor movement, which has just been published in Mother Jones magazine. I wrote an essay to accompany the project. Please check out the full package of photos, they’re great. Also this week, I wrote a piece for In These Times about the danger of the recent era of abundant labor reporting coming to an end, unless we find new sources of financial support for labor journalism.

—My book about the labor movement, “The Hammer,” is officially a USA Today bestseller, which I recently learned is a list that exists. I have been on book tour, meeting many of you and talking about how to get this fucking movement popping, which has been a fantastic experience. Please come out to one of my upcoming events if I’m in your area:

Monday, March 18: Philadelphia, PA—At the Free Library of Philly, 7:30 pm. With Kim Kelly.

Thursday, March 21: New Orleans, LA—At Baldwin and Co. Books, 6 pm. With Sarah Jaffe. Free tickets are here.

Wednesday, March 27: Boston, MA— At the Northeastern College of Professional Studies at 101 Belvidere Street. 6:30 pm. Free tickets are here.

Sunday, April 21: Chicago, IL— “The Hammer” book event and Labor Notes Conference after party at In These Times HQ, 2040 N. Milwaukee Ave. 5 pm.

I’m also planning some California events for April, so stay tuned. If you’re interested in bringing me to your area to speak, email me.

—As I touched on in In These Times this week, the economic model of the journalism industry is in full collapse. This publication, How Things Work, is my small attempt to forge a new model. This place can only exist because of paying subscribers. If you’d like to support my work, please consider becoming a paid subscriber today. Thank you.

"I wish they would learn and embrace the importance of being in a union, especially when you work in journalism. Most newspaper owners aren’t journalists, they’re business people. They will make decisions that benefit them but not necessarily ones that benefit their employees."

My wife is a travel nurse. She's been travel nursing for the last 6 years. In that time, she's been offered exorbitant contracts at hospitals whose nurses are on strike. But she won't take them because she refuses to be a scab. And this -

" When you cross a picket line, not only are you showing how much you don’t respect the strikers and their work, you’re also showing how you don’t respect yourself or your work."

Is why. She refuses to take the side of management against members of her own profession.

Thank you for bringing us this interview.

"From what I understand, the NLRB is very understaffed and very busy, so we’re still waiting to hear back on that…"

Given that the NLRB is so understaffed it can't manage the labor situation in a country with ~10% union membership, and given that the stated goal is 100% union membership, given that this is the case under ol lunchbucket photo op joe, given that under any later republican administration & probably democratic ones it will be even more underfunded and feckless where not jammed full of actively hostile stooges, seems like people are gonna have to get themselves used to wildcat strikes, and whatever else it might take to force the bosses to the bargaining table.